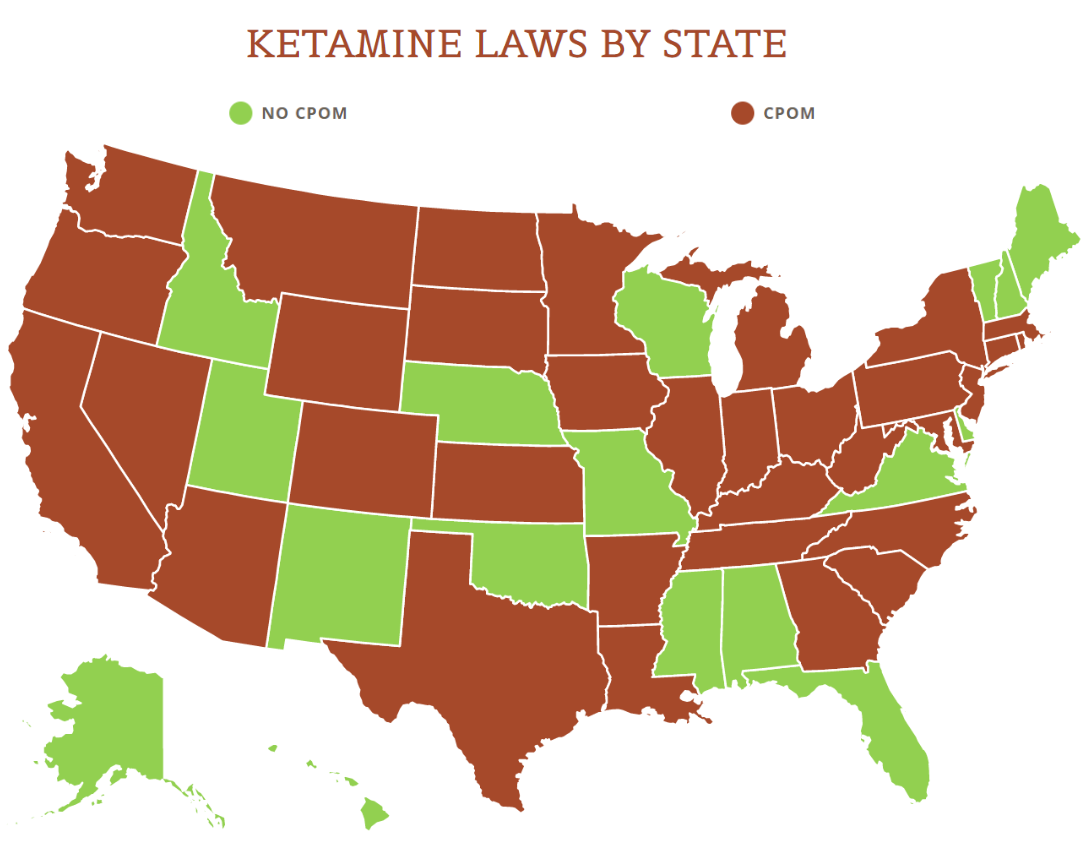

As we have written about before, the corporate practice of medicine doctrine (“CPOM”) is a creature of state law (click here to review a prior post on CPOM). While some states do not have a CPOM doctrine (like Florida), other states have very strict CPOM doctrines (like New York and California). At its core, CPOM prevents lay individuals and lay entities from directly venturing with healthcare providers, and it likewise prevents a lay entity from employing healthcare providers. The reason is clear – no one wants their healthcare providers answering to lay individuals who are not versed in clinical care. So, in those instances where CPOM prevents these activities, lay individuals and lay entities form Management Services Companies to assist providers with non-clinical activities (e.g., billing, employing non-clinicians, providing clinic space and supplies, etc.).

The Origins of CPOM in Arizona

In Arizona, the CPOM doctrine is based on old case law. In Funk Jewelry Co. v. State ex rel. La Prade, 46 Ariz. 348, 50 P.2d 945 (1935), the Arizona Supreme Court reasoned that the inability of a corporation to obtain a license to operate a store that employed an optometrist made such a practice illegal. 46 Ariz. at 351, 50 P.2d at 946. Because “[t]he defendant company could not conduct a business without a license” and the state had “the right to exclude any individual from practicing such profession unless he had met the statutory qualifications and obtained a license from the state,” the Supreme Court concluded that the defendant “is violating the law regulating optometry” by operating a store without such a license. Id. (citations omitted) (internal quotation marks omitted). The Funk decision was reaffirmed in later decisions. While Funk dealt with an optometrist, the prevailing wisdom is that the decision applies to anyone practicing healthcare, whether a dentist, physician or any other type of healthcare provider.

View the US Map of Ketamine Legality

Midtown Medical Group Decision

In 2008, the landscape changed in Arizona. While the Funk decision and its progeny remains good law in Arizona, there is now an Arizona Court of Appeals decision that opens the door for investors to directly venture with healthcare providers, and to also employ those providers.

In Midtown Medical Group, Inc. v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Co., 220 Ariz. 341 (App. 2008), the Court of Appeals was asked to decide whether an “outpatient treatment center” as described in Arizona Revised Statutes (“A.R.S.”) section 36-405(B)(1) and Arizona Administrative Code (“A.A.C.”) R9-10-101(39), which employs physicians and chiropractors, may be owned by persons who are not licensed physicians or chiropractors. The Court of Appeals answered this question in the affirmative, thus allowing this arrangement to stand.

The Court of Appeals analyzed various statutes and regulations that had been amended well after the Funk decision. The Court of Appeals found that the plain language of the amended regulations clearly authorized a corporation to be licensed as an “outpatient treatment center.” Moreover, the Court of Appeals further found that the amended statutes and regulations did not require a “natural person” to hold a professional license to obtain an Arizona outpatient treatment center license for such an entity.

Generally, a clinic does not need to be licensed in Arizona if healthcare providers have at least a 50.01% ownership interest. However, in instances where a clinic is owned by lay individuals who have at least a 50.01% ownership interest, then it must hold an outpatient treatment center license. As the Court of Appeals noted:

…if a physician owns a private office or clinic that is providing services such as those specified for an “outpatient treatment center,” the licensed physician need not seek licensure from the Director [of the Arizona Department of Health Services]. Indeed, the typical physician’s office is a virtual parallel to the definition of an “outpatient treatment center”: an entity “without inpatient beds that provides medical services for the diagnosis and treatment of patients.” A.A.C. R9-10-101(39). This leads to the inescapable conclusion that the intent of the licensing statutes and regulations providing for “outpatient treatment centers” was to expressly regulate and permit what [the Defendants] would seek to preclude: the ownership of such an entity by persons (whether individual or corporate) who themselves do not hold a license to practice in the medical or health care field for which “medical services” are provided.

However, because the Midtown Medical Group was decided by the Arizona Court of Appeals, the Court of Appeals could not overturn the Arizona Supreme Court’s decision in Funk and its progeny. Thus, the Court of Appeals found a narrow exception to the CPOM doctrine in Arizona for “outpatient treatment centers.” As the Court of Appeals noted:

Based on the statutory and regulatory scheme pertaining to “health care institutions” generally and “outpatient treatment centers” in particular, the holdings of Funk and Sears do not determine the outcome in this case. In reaching this conclusion, we emphasize that our decision is a narrow one. We have no authority to modify, and do not modify, any portion of Sears and/or Funk. We likewise make no pronouncements as to the general vitality of the doctrine of the corporate practice of medicine. We address and rule upon only the narrow issue presented to us: that the statutory and regulatory scheme pertaining to “outpatient treatment centers” expressly permits the Director [of the Arizona Department of Health Services] to issue a license to a general corporation whether or not that corporation is owned by individuals with a separate license to practice in the health care field at issue.

Conclusion

While CPOM continues to exist in Arizona, at least for outpatient treatment centers (like ketamine clinics) there is now a path forward for co-ownership between medical professionals and lay entities, as well as the right for lay entities to employ healthcare providers. While it is possible that the Arizona Supreme Court will be asked to review these issues, it seems that the Court of Appeals rationale would likely prevail and be upheld.