Contents of this Article

- BRI countries will need increased economic activities to pay back Chinese debt

- Africa’s greatest opportunities in business

- How is Africa reacting to China’s increasing presence through its Belt and Road Initiative?

- Does Africa present a viable alternative to companies that want to move manufacturing from China?

- Which African nations are most welcoming to Chinese development projects?

- What most concerns you regarding the current state of African development?

- How important are the geopolitics of Africa to current and future business prospects in Africa?

- What does Africa need that foreign companies can provide?

- What does Africa have that foreign companies need?

- Can you give examples of industries in which Africa is doing well and in which it will likely emerge as a global leader?

- What should foreign companies consider when making their first foray into Africa to do business?

I like to keep company with savvy international people with expertise that complements mine. My longtime friend, David Baxter, is one of those people. He is a South African who now lives in the Washington, D.C. area but routinely travels all over the world to advise governments and companies as an international development consultant. I call him “Mr. PPP” (Public Private Partnerships) because one glance at his LinkedIn profile makes that clear. As Mr. PPP, David specializes in public development projects in Africa, the Middle East, Asia, and everywhere else, which gives him insight into how governments are fostering international business, which governments are serious about international development, and which ones are smart about it. When speaking with David, we concocted a series of Q and A questions about the impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative from David’s boots-on-the-ground perspective.

BRI countries will need increased economic activities to pay back Chinese debt and will welcome U.S. and foreign companies that want to use their new infrastructure in both import and export ventures

The goal is to help U.S. and international companies understand what China is doing in target international markets so that they can benefit from utilizing Chinese-funded or Chinese-built infrastructure. As David put it, “Increased traffic using those facilities is in the national government’s interest, and those facilities are ready doors to enter into many regions. Why aren’t companies looking at opportunities where they’re using Chinese infrastructure in these foreign markets?”

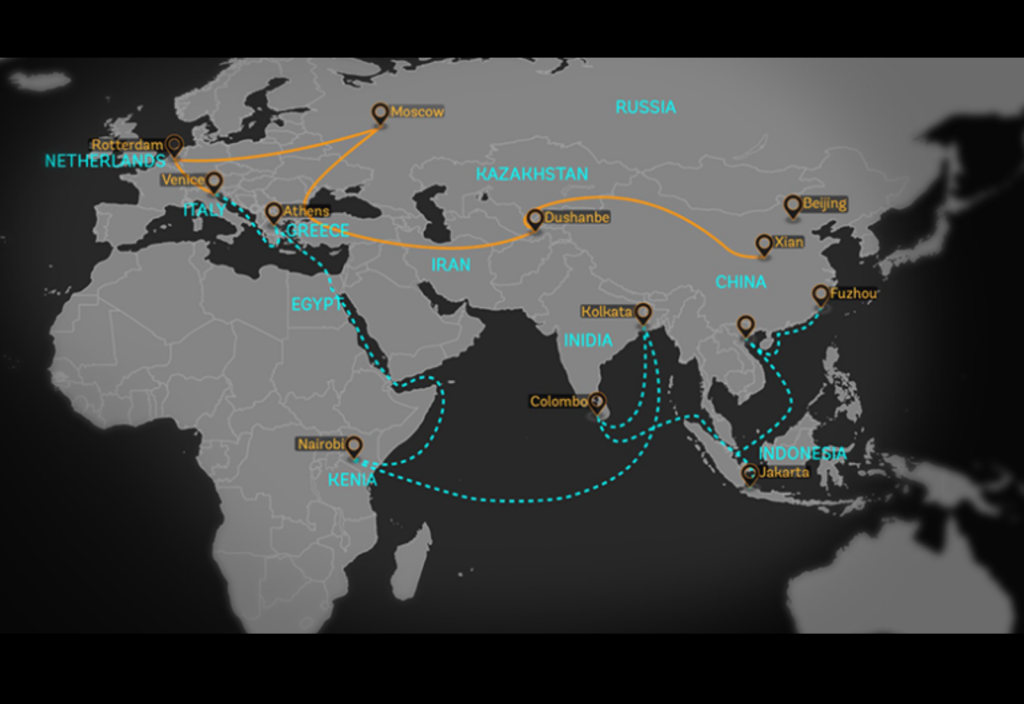

Since 2013, China has been busy making friends through its Belt and Road Initiative (“BRI”). China aims to encircle countries in the historical overland Silk Road and new maritime Silk Road in interconnected infrastructure to bring them closer into China’s realm of influence and provide a host of mutual benefits to China and the involved countries. China provides long-term, low-interest loans to governments and often provides the lowest priced skilled labor required for those projects.

As of May 2019, over 60 countries have agreed to or expressed interest in BRI projects, and those countries encompass about 2/3 of the world’s population, representing both potential markets for Chinese goods and potential labor pools for lower-cost labor. They represent a large portion of the world’s natural resources, which can provide raw materials to feed China’s manufacturing complex. These countries include Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Myanmar, Laos, New Zealand, Iran, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, Egypt, Ethiopia, South Africa, Russia, Poland, Ukraine, and many more (see CFR’s Belt and Road Tracker for the full map, and CSIS’ interactive map is also excellent). These countries include many of the global energy producers (Middle East and Russia) and energy consumers (developing nations). Because China is an export-focused economy, it cannot let up its current pace of development. It needs to keep its SOEs and workers busy, either on domestic or international projects, or both.

But like all friendships that come with strings attached, many countries have started to feel uneasy about chummying up too close with their lender. In China’s BRI, in which China shows up with a checkbook, an open handshake, and a Xi Jinping-worthy smile (especially when that relationship sometimes mandates Chinese firms be included in the bidding process) those strings can feel more like chains. Debt trap diplomacy is a term that has been used to describe China’s BRI projects because China has been willing to extend loans on outwardly favorable terms with plenty of recourse for China if the borrowing nation defaults.

Due in part to this type of heavy-handed diplomacy, U.S. and foreign companies have opportunities to make inroads into these countries and markets. The Chinese are building ports, roads, rails, and power plants, along with cables and pipelines, but they do not control who uses the infrastructure. And because China’s BRI investments often bring additional cultural and political baggage, some target countries are loathe to fully engage with China. China’s “big brother” oversight through both technology and individuals on the ground and Chinese information (and disinformation) networks disguised as cultural enrichment programs, together with the prospect of Chinese colonization by leaving its workers in-country are just some of the concerns of BRI partner countries. Many of these BRI countries will need increased economic activities to pay back their Chinese debt and will welcome U.S. and foreign companies that want to use their new infrastructure in both import and export ventures. Those countries with ports, energy infrastructure, and a willing (trained or trainable) labor force will be most attractive to companies in maritime countries like the U.S. who know that maritime transport is a fraction of the cost of overland transport.

In sum, China is looking at the long game, and so should your company. (For instance, China’s state-owned Chinese Overseas Ports Holding Company has a long-term lease on Pakistan’s Gwadar Port through 2059, but in Chinese consciousness, anything less than 1,000 years is short-term planning.) If your company does not have a 40- or 50-year plan, it should start to think in those terms. China’s long-term BRI infrastructure development is a boon to companies who are looking to engage with new international markets for raw materials, a deeper labor pool, and potential consumers. In our future posts, we’ll do our best to help you recognize and utilize the most promising BRI markets, including identifying the best enabling environments and potential legal issues.

Africa

You have spent a large portion of your life in Africa, which has historically been exploited by colonial powers. How do today’s Africans view themselves, their countries, and their continent with respect to the rest of the world? In other words, what is Africa’s current “social consciousness”?

When I was in Uganda recently, I heard pragmatism among Africans, about their past, current, and potential future problems. But I routinely hear enthusiasm among Africans who are becoming more educated and skilled. They believe that they can make this century “Africa’s century.” To me it seems like the more they have been poorly treated, the more determined they have become to build Africa with African objectives for a strong African future. Africans want relevant, sustainable growth for Africa. Mostly when I talk about Africa, I am referring to sub-Saharan Africa, not Arab North Africa which forms part of the MENA (Middle East, North Africa) Region. The enthusiasm that I am referring to is regional in nature: West Africa (e.g. Ivory Coast, Ghana, and Nigeria); East Africa (e.g. Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, and Kenya); and Southern Africa (e.g. South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Mozambique, Zambia, and Zimbabwe). Each region has different opinions and approaches to its development path. East Africans are probably the most enthusiastic and pragmatic about development strategies because they have less resources than their counterparts in other regions. They believe they must do a lot with little. West Africans, particularly Nigerians, know their country is such a juggernaut, so they feel that they can accomplish almost anything. However, they know they face corruption related to oil revenues: weak governance and bad investment decisions. They stoically recognize their missteps, and they’re trying to fix them. I am from South Africa, where some South Africans are unfortunately stuck in a post-Apartheid political paradigm that has stalled forward progress. Fortunately, most of the younger post-Apartheid generation are focused on looking forward, not backwards and are embracing economic innovations that will help lift Southern Africans out of their current challenges. Africa has some dysfunctional countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Central African Republic, which are prone to misadventures when it comes to development. Because they are desperate for investment in development projects, they are more prone to exploitative “good deal” that is not in their national interest. In many cases, the leadership of these countries have mortgaged their future for ill-conceived projects that have poor long-term prospects. However, Southern Africans, Western Africans, and Eastern Africans are becoming more discerning about how they engage with investors. They better understand the types of projects they need, and what should be the long-term objectives of realistic strategies (usually tied to sustainable development goals). Landlocked countries are particularly tied to the fates of their coastal neighbors, and this is driving regional integration efforts. This can be both advantageous and disadvantageous for those landlocked countries, depending on their neighbor’s willingness to develop common development objectives.

What do you see as Africa’s greatest opportunities, either for African companies or foreign companies looking to do business with Africa?

Africa is beginning to shine in leapfrogging technology: cellular networks, renewable/sustainable energy, and telecommunications have all flourished because countries did not have to invest in outdated infrastructure for these new technologies. Renewable energy (i.e. photo-voltaic power generation) does not require big power grids, for example. They can utilize small, off-grid systems. Solar and hydro are being developed throughout Africa, and geothermal specifically in East Africa. I see a lot of PPP/infrastructure projects emerging in those sectors. South Africa and Rwanda are becoming service-focused economies with call centers and technology centers. They have the expertise, which helps their neighbors, as well. There has always been a political focus on pan-African projects to connect and integrate Africa: trans-Africa highway projects (the Cape to Cairo road has been a dream for hundreds of years; also, east-to-west access routes for trade). These transnational connections that will integrate economies and allow them to share resources is becoming a greater focus of governments. Air transportation is still a challenge in Africa. In some regions people must fly via Europe to reach their neighbors. The biggest growth is in developing railway networks and transnational highways. Big rivers like the Congo River and Niger River are being revisited as routes to trade goods and access raw materials. Ironically, these rivers, which were first used in the colonial era, saw their ferry and river transport infrastructure fall into disuse. Now Africans are beginning to realize that river transportation can be an infrastructure backbone for countries like the Democratic Republic of Congo if their supporting infrastructure is revitalized through investment.

How is Africa reacting to China’s increasing presence through its Belt and Road Initiative?

It is a mixed bag. East Africa has two big projects that have been teetering on failure. In a transnational railway project that was supposed to connect Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda, things stalled after their governments said the project was too expensive. When they said that they could not afford the debt burden, Chinese investors pulled out, citing project risk. The project is half finished, and now it is called the “railway to nowhere.” The new Addis Abba, Ethiopia to Djibouti railway to the Red Sea was completed. It was built and financed by the Chinese, but the Ethiopian government now faces excessive debt because it paid more for the debt that these projects incurred than they should have. Africans are beginning to realize that these types of procurements are not transparent or competitive. Many governments are now questioning how these types of projects bind these countries to foreign economic interests, not domestic development interests. Generally, Africans are a little more apprehensive about enthusiastically agreeing to proposed terms from unsolicited infrastructure deals. However, irrespective of this, China is increasingly making inroads Africa. China is beginning to recognize it needs to offer better deals, especially in countries with more vibrant African democracies. Where governance has changed hands through the ballot boxes rather than coup d’états, these new governments are stronger. But countries that lean more toward authoritarian leaders, like the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo, grabs onto a Belt and Road project as a short-term way to show their country’s citizens economic growth without explaining the long-term future implications. These short-term vies are resulting in the “sale” of national resources to the Chinese investors with dire consequences if they default on their loans. This “debt trap” is a big discussion in Africa. There are also concerns that Chinese businesses will squash local businesses where Africans are not as well skilled, trained, educated, or experienced in the craft of competitively doing business. In some African countries, goods that are cheap, made in China, and sold by Chinese businessmen are suffocating local businessmen. Consequently, U.S. and other foreign countries with strong social corporate responsibility practices will find Africa an inviting market. It is an enormous market that will grow exponentially in the next 20-30 years. The demographic momentum is there. Even with zero marketing, companies will find that there is already a great demand for durable goods.

Does Africa present a viable alternative to companies that want to move manufacturing from China?

Many products manufactured in China could be manufactured in Africa. Textiles, shoes, and glassware could easily be produced in Africa. The key is to find partners in countries that have created an enabling environment, meaning that the country is stable for foreign competitive and transparent investment. Companies should focus on the ease of starting up business indices, which vary from country to country. Many Southeast Asian countries are no longer inexpensive labor markets, but there are still inexpensive labor markets in many regional hubs in Africa. These hubs contain skilled people seeking jobs and a rapidly growing middle class. These African countries present great opportunities to build a sustainable market base. Some US companies have been in Africa for over a hundred years. Companies like Coke, Ford, and IBM know about Africa’s potential and have done well there, and their market penetration strategies should be emulated.

Which African nations are most welcoming to Chinese development projects? Are these same countries also welcoming to U.S. and European companies?

Poorer countries like Mozambique, Somalia, and Sudan are some of those that have welcomed China. More developed African nations have been pushing back against China. African countries with strong anti-corruption policies and competitive and transparent procurement practices are more interested in doing business with Western companies. Chinese companies typically want handshake deals; they often do not want transparency or competition. Countries with good legal frameworks and enabling environments (e.g. South Africa and Ghana) have great potential and present a better chance for Western companies to compete because deals are not being made behind closed doors. Studying and utilizing the World Bank’s ease of doing business index will be helpful in selecting good markets to enter. Countries with strong contract enforcement and less strict controls on repatriation of profits will be more attractive to Western companies. Many African countries have laws with strict profit remittance controls. These restrictions do not bother the Chinese companies because they generally do not remit money back to China; they remit raw goods to their home country instead.

What most concerns you regarding the current state of African development?

Africa’s public sector funding gap is its biggest challenge. Countries have significant needs, such as hospitals, schools, road, bridges, but they do not have the funds to build them. Sectors such as healthcare, education, water, wastewater disposal, energy, and transportation are already a big focus. These generally enhance the sustainable development goals of the UN and require business partners that support sustainability and resilience. There is great potential for Western companies with responsible market policies. The current Chinese and Indian consumer markets will be dwarfed by the end of this century by Africa’s domestic market demands. This demand, supported by a movement to develop free trade zones, will enhance African development objectives by encouraging these countries to work together, integrate their economies, and share resources in sub-Saharan Africa.

How important are the geopolitics of Africa to current and future business prospects in Africa?

Pan-African identity is continually evolving. The countries and markets may be inclusive or exclusive. It is important to pay attention to how different regional blocks or customs unions develop. Will they collaborate or will they compete with each other? Which foreign companies will gain footholds in these post-colonial regions? The Chinese are present across Africa. So are the French in Francophone West Africa. Former British colonies (Commonwealth countries) comprise their own geopolitical unit, as do the Lusophone colonies (colonized by the Portuguese) and the Saharan African blocks. The African Free Trade Zone has not developed yet because of the disparate geopolitical aspirations among these regions. The rule of law is significant due to the starkly different legal structures present. For instance, some countries operate under the “Napoleonic code” (French Colonies). Others operate under Roman/Dutch law, like South Africa and its immediate neighbors. Then you have the English common law, along with the legal philosophies and practices. Similarly aligned countries are well positioned to do business across borders, but there are still complexities in procuring large transnational infrastructure. Overall political stability is a significant factor. Look at East Africa – the Somalia/Somaliland split is problematic and needs to be resolved. The Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Central African Republic essentially do not even exist as functioning states. Their boundaries were drawn by foreign powers in Berlin a hundred years ago, and these regions are facing difficult issues centered around the different ethnicities of their people. The typical Western company will be better off to focus on the African countries that have had multiple successful democratic elections resulting in progressive leaders who provide political and economic stability.

What does Africa need that foreign companies can provide?

Africans need Western innovation and new technology. Western companies need partners in countries that have a strong rule of law to protect these valuable business investments in infrastructure.

What does Africa have that foreign companies need?

Africa’s burgeoning middle class makes for a large and growing consumer market, and the rapidly increasing number of well-educated Africans needing employment make for a strong workforce. Africa can provide both skilled and semi-skilled labor to meet most any company’s needs.

Can you give examples of industries in which Africa is doing well and in which it will likely emerge as a global leader?

Africa currently excels at producing basic essentials, such as textiles and shoes. Vehicle manufacturing is growing. Japanese and German companies established large auto manufacturing facilities in South Africa years ago, and Africa now exports Toyota, Nissan, and Mercedes-Benz vehicles to their countries of origin. Petrochemicals will be big for a long time. Tanzania and Mozambique recently discovered oil and gas reserves. In Uganda and Kenya’s Rift Valley they have been developing numerous renewables: geothermal, solar, wind, and hydroelectric energy. Africa’s ports are important for its import and export economies, including for landlocked countries. Africa has the most landlocked countries in the world, and the growing transportation infrastructure that can unlock those countries will be important. Unfortunately, Africa’s airline industry is problematic and has a long way to go.

What should foreign companies consider when making their first foray into Africa to do business?

You need reputable local partners. It is difficult to get into certain countries without them. I am not talking about “fixers” or “facilitators” who will lead your company toward a path of corruption. Do not assume Africa doesn’t have skilled people. South Africans are highly skilled. Namibia is very advanced; Rwanda is quickly becoming the IT hub of Africa. Reach back into the African diaspora for assistance from people who live in your home country — people like me. Do not hire foreigners who know little about the complexities of Africa. For example, the Nigerian expat communities in the U.S. and in Europe are enormous and can offer much. There is a large Ethiopian community here in D.C. and in various other cities in the United States and Europe. Many of these Africans have come to the U.S. and other Western countries and become trained as professionals, and many are looking for opportunities to invest their time and money in their home countries in Africa. They are looking to collaborate with U.S. companies in those future opportunities. Western companies have largely ignored the opportunities that members of the African diaspora offer.

Africa is ready to do business with the world.

The World Bank’s 2019 rankings for ease of doing business can be found here, with the following African countries in the top 100:

38. Rwanda

53. Morocco

56. Kenya

78. Tunisia

84. South Africa

85. Zambia

87. Botswana

97. Togo