The Oregon psilocybin program has a residency requirement. I explained how it works here, and wrote “queue the crazy business structures.” Because the program is off to a slow start (see here and here) I haven’t received as many crazy requests as expected. Well, that changed last week when I received a proposal that made my head spin.

All of this got me thinking about a blog post I once wrote for our sister blog, the Canna Law Blog. That post was deleted, but I was able to find a pirated copy on some virtual grifter’s domain. I won’t assist that grifter with a link; but I’m glad they stole my work after all, because it allowed me to salvage and repatriate that piece below.

One more introductory comment: I realize psilocybin mushrooms are very different from the cannabis plant. Legally, however, there is a lot of crossover. Both are the object of state licensing programs, and both are schedule 1 controlled substances at the federal level. Psilocybin and cannabis businesses are both subject to punitive taxation under IRC §280E. And they are both attractive, at times, to parties who wish to participate in state-licensed programs undercover, or, in the worst cases, to use these novel programs for fraud.

In short, everything written below as to cannabis businesses applies equally to Oregon psilocybin businesses. Please enjoy, and please be careful out there!

The Cannabis Business Structure Hall of Fame (with Pictures)

We have worked with, in and around cannabis companies for a decade here at Harris Sliwoski. In that time we have been privileged to advise and structure some truly impressive enterprises. Conversely, we have also seen all manner of malfeasance, nonsense, and fraudulent scheming. This post explores the latter. Specifically, it covers a personal grievance I’ll refer to as “obfuscating structures.”

Often, we see obfuscating structures when someone hires us to review a potential investment opportunity. Other times we are brought in late, when people have begun to argue about something unfortunate that happened in one of these structures. A pile of money has inevitably disappeared; no one really knows how; no one knows quite where to start.

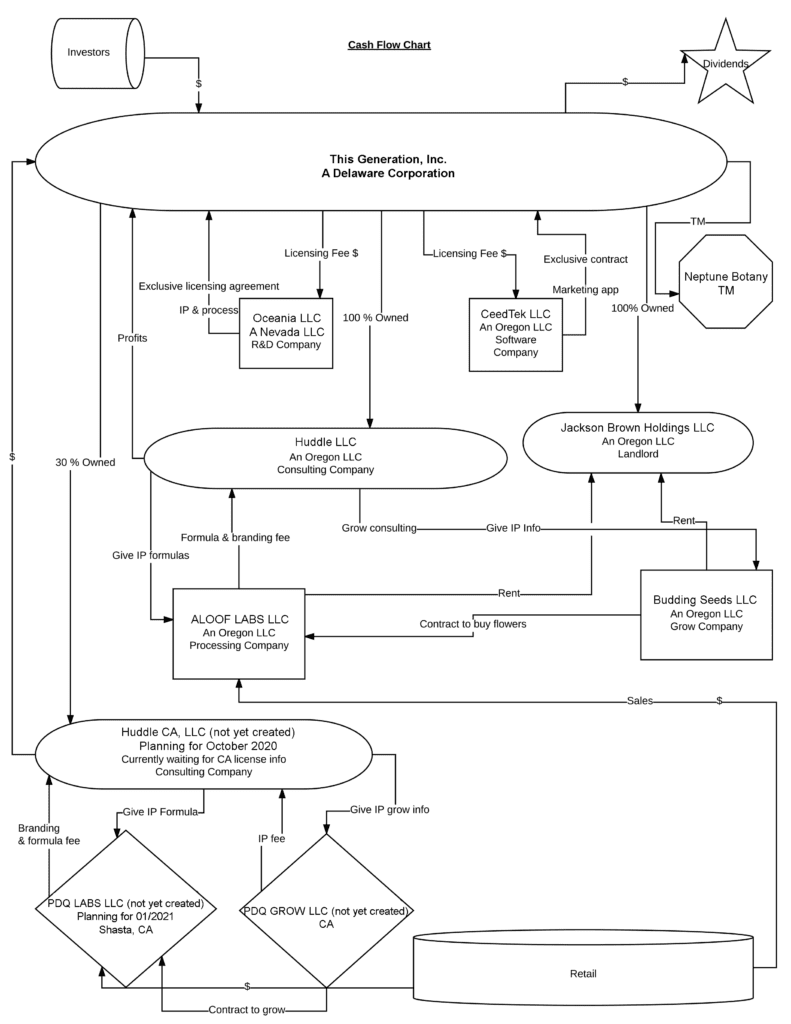

The “Cash Flow Chart” immediately below is a real beauty. It was built by someone who was either wildly optimistic or a huckster. Our client in this fiasco was a hapless manager and director of one or more of these companies. He was sophisticated in horticulture but not in business. He also had monied family connections, and he and they had been lured in by the wild optimist/huckster.

All names above have been changed to protect the innocent. To be clear, though, this was one pile of money ($2 or $3 million, at most) to somehow capitalize and link up, across states: a holding company, a real estate holding company, a research company, a software company (!), a few labs, a consulting company, a licensing company (or two?), a farm and a store. These things were owned in varying degrees by various people, but especially the huckster.

When this client came to us, money had disappeared and none of these businesses were operational. Some of the entities were dissolved or inchoate, and none had bank accounts or even QuickBooks files. Some had basic — but glaringly inconsistent — internal agreements. People may or may not have taken “director fees” and “consultant fees.” Others were writing brazen and ill-advised emails. Etc.

When you have a chance to interview the esteemed architects of structures such as these, you may come across a few stated reasons for the complexity. The first is ostensibly a desire to create and control a very specific type of supply chain or ecosystem, often grounded in plant genetics. The theory here is that operators and investors in the “closed loop” ecosystem will benefit handsomely by controlling exclusive intellectual property (IP) all the way to retail. Sounds great, right? It almost never works. Aside from the generally nebulous nature of cannabis “plant IP”, the cannabis industry is capital intensive and highly fragmented. These things are very, very difficult to pull off.

The second impetus for obfuscating structures (aside from common fraud) may be tax avoidance. People build complex structures to move revenue away from “trafficking” entities and mitigate IRC §280E tax impacts. This also seldom works. The whys and wherefores are many and vast, but suffice it to say that: 1) except for Champ v. Commissioner (“CHAMP“) no cannabis taxpayer has won a §280E case (and there have been a bunch of them); 2) a taxpayer is exposed to a 20% understatement penalty if he/she/it signs a return that is not supported by “substantial authority”; and 3) the IRS will always look at the substance of a structure or transaction, rather than its form.

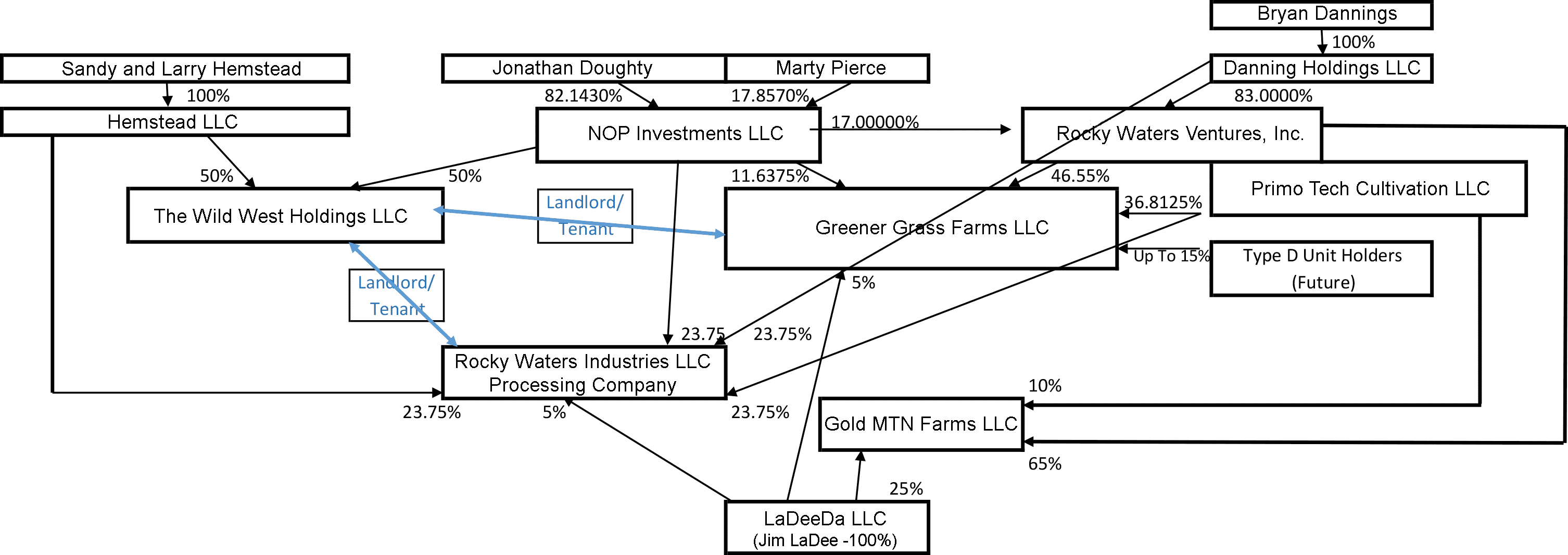

That said, people try crazy things. Here’s another mastermind at work (again, names have been changed):

I trot out this particular example because the architect was an experienced CPA. The CPA got a lawyer to stand behind it and one key investor to invest (for all the nonsense you see above, there were really just four or five “people” involved in this apparatus). We represented the investor as the apparatus failed spectacularly over a period of years, spawning multiple litigations and threatened litigations. The lesson? Even credentialed professionals may promote these rats’ nests.

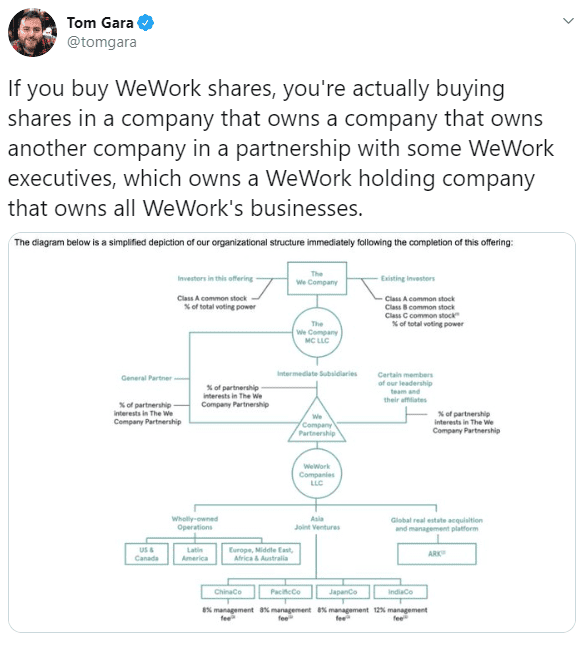

Unfortunately, many people have invested in cannabis companies over the years without really understanding what they are buying. That’s true of small start-up schemes but it’s also true of larger, publicly traded businesses. And sometimes it’s hard to fault the investors, especially when the pitch comes from an acquaintance and the business or structure hasn’t begun to operate or generate financial statements. People see a service or product and they rely on promoters to place their bets, regardless of apparent complexity. Remember last year’s WeWork pitch?

That one turned out to be problematic in analogous ways. WeWork was further along of course, but fundamentally the concept was oversold, over-designed and financially unsound. WeWork may have been better papered, but what you see above is an obfuscating structure. In that sense it is similar to many early- and mid-stage cannabis plays.

So what are the big takeaways here?

For company founders and promoters, keep it simple to start. For tax planning purposes, stay within the CHAMP guardrails. Or really, truly understand CHAMP and the gory details of each subsequent §280E case before you structure your enterprise. For everything else, build the spaceship piece by piece. And as you build, make sure each part has a well-papered purpose that isn’t naked tax avoidance or extreme promoter enrichment.

For investors, make sure you really understand what is going on with all of those entities and arrows. When you put a dollar in, where and how should that dollar come out? If the scheme cannot be simply and satisfactorily explained to you or a trusted advisor, run! Otherwise you could become an unwitting casualty of the Cannabis Company Structure Hall of Shame.