Ketamine clinics are run by various provider types in the United States. In some states, mid-level practitioners (e.g., Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants) can practice independently. In other states, such providers can only work independently if they are supervised or overseen by a physician. However, the question then becomes whether any physician can run a ketamine clinic without exposing themselves to increased liability? If a dermatologist decided to open a ketamine clinic, is her training sufficient to treat patients with behavioral health issues, pain disorders, etc.? The answer depends on a variety of circumstances. And the implications of practicing beyond a provider’s expertise can be severe.

From what we have seen in the market, ketamine clinics typically follow one of two models. There are clinics where no referral is required by another provider, and the ketamine clinic is the sole source of therapy for that patient. The other type of clinic coordinates with other providers as part of a continuum of care. These providers typically require referrals from another health professional and likewise coordinate their care with those other providers. We see these issues most often when it comes to behavioral health, although other medical conditions likewise can be problematic. While there are generally two approaches, there is a lot of variation within each type of model.

Certainly, a physician who is providing ketamine treatments as part of the patient’s overall care plan is likely to have less exposure to medical malpractice and ethical issues. And the safest set of circumstances would be for a psychiatrist to be the treating physician at the ketamine clinic as one part of the patient’s behavioral healthcare needs. However, we have rarely seen psychiatrists opening and running ketamine clinics. Instead, it is primarily other specialties, including anesthesiologists, emergency room physicians, internists, etc.

Ketamine clinic malpractice issues

While each state may have different legal standards for a medical malpractice action, the norm is the provider must meet the local or community standard of care. To our knowledge, there is no national standard of care established for ketamine clinics. Although, there are healthcare provider trade associations that have published non-binding recommendations for the standard of care.

Here in Arizona, the basis for a medical malpractice action is partially set forth in the Arizona Revised Statutes (“ARS”). Seisinger v. Siebel, 220 Ariz. 85, 95 (2009) (“[t]he common law elements of a medical malpractice action have now been partially codified by the legislature in A.R.S. § 12–563.”). Generally, in Arizona, a “medical malpractice action” means an action for injury or death against a licensed health care provider based upon such provider’s alleged negligence, misconduct, errors or omissions, or breach of contract in the rendering of health care, medical services, nursing services or other health-related services. ARS § 12-561(2). To prove a physician caused a medical malpractice injury, the plaintiff must show, among other things that:

Both of the following shall be necessary elements of proof that injury resulted from the failure of a health care provider to follow the accepted standard of care:

- The health care provider failed to exercise that degree of care, skill and learning expected of a reasonable, prudent health care provider in the profession or class to which he belongs within the state acting in the same or similar circumstances.

- Such failure was a proximate cause of the injury.

ARS §§ 12-563(1) & (2).

To understand any legal standard, there is a lot of parsing that happens. Generally, though, the foregoing is enough to demonstrate some of the basic elements for a medical malpractice claim in Arizona.

If we focus solely on whether a physician failed to exercise the appropriate degree of care, skill, and learning required of a reasonable physician, it can be illuminating for ketamine clinic services. Would it be reasonable for a dermatologist to perform neurosurgery? Would it be prudent for a radiologist to perform a colonoscopy? While these are extreme examples, they demonstrate the danger of practicing outside of a physician’s formal training and board certification. However, again, those physicians that practice as part of a continuum of care have less exposure.

Conversely, there are arguments for why most physicians can provide ketamine treatments without specialty training (for those providers who do not participate in a continuum of care). Assuming the provider’s training includes diagnosing certain disorders, then one impediment is removed. However, the next question is whether the provider has the expertise to also consider other possible treatments when deciding that ketamine is the optimal or appropriate treatment for a patient. Administering intravenous ketamine would presumably be within all physicians’ skill sets. These are just a few of the issues to consider when evaluating the risks for physicians.

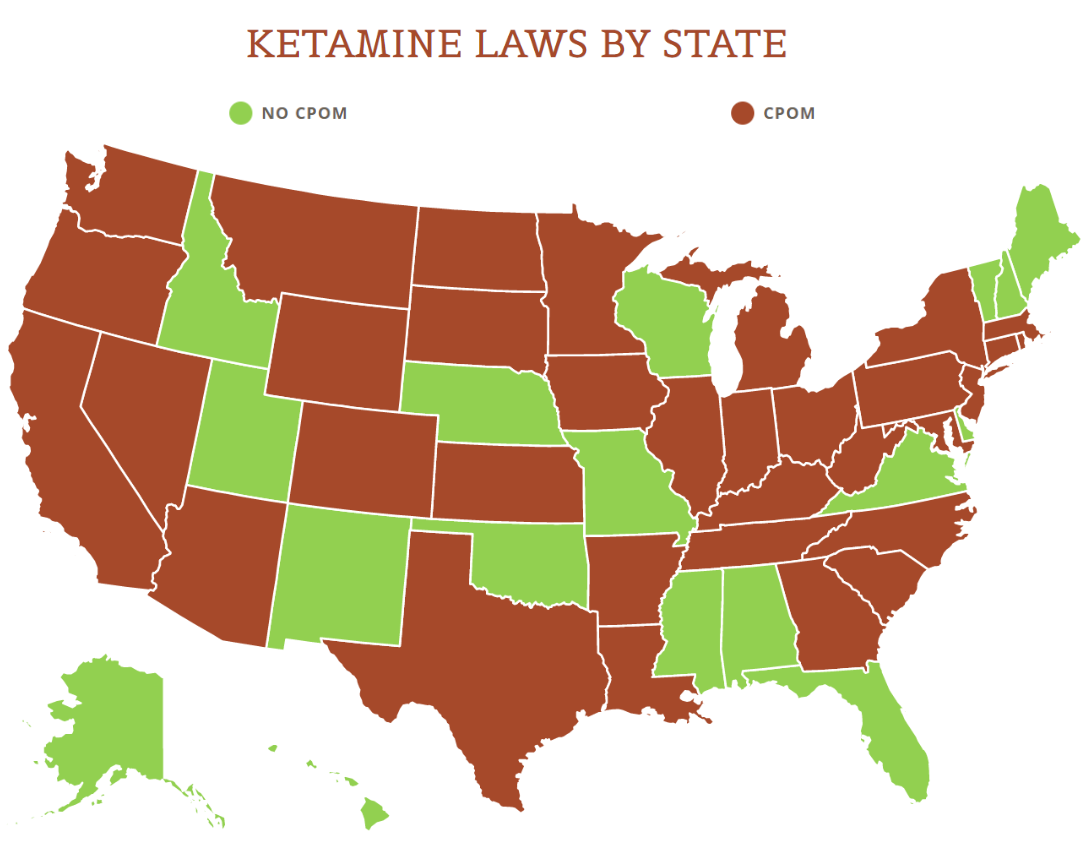

View the US Map of Ketamine Legality

Ethical issues and board action

The next issue to consider is whether treating a patient under the foregoing circumstances is unethical. In Arizona, the statutes define “unprofessional conduct” for physicians, and the definition provides a long list of prohibited activities. If a physician is found to have committed unprofessional conduct, the Arizona Medical Board has a variety of punitive (and/or corrective) measures it can take, leading up to and including, revoking a physician’s license to practice medicine.

In terms of the issues discussed in this post, below are some examples of unprofessional conduct in Arizona that could be applicable:

- Committing false, fraudulent, deceptive or misleading advertising by a doctor of medicine or the doctor’s staff, employer or representative.

- Prescribing, dispensing or administering any controlled substance or prescription-only drug for other than accepted therapeutic purposes.

- Committing conduct that the board determines is gross malpractice, repeated malpractice or any malpractice resulting in the death of a patient.

- Committing any conduct or practice that is or might be harmful or dangerous to the health of the patient or the public.

- Knowingly making any false or fraudulent statement, written or oral, in connection with the practice of medicine.

- Obtaining a fee by fraud, deceit or misrepresentation.

- Using experimental forms of diagnosis and treatment without adequate informed patient consent, and without conforming to generally accepted experimental criteria, including protocols, detailed records, periodic analysis of results and periodic review by a medical peer review committee as approved by the United States food and drug administration or its successor agency.

- Representing or claiming to be a medical specialist if this is not true.

- Committing conduct that the board determines is gross negligence, repeated negligence or negligence resulting in harm to or the death of a patient.

ARS §§ 32-1401(27)(c), (j), (m), (r), (u), (w), (z), (cc) & (mm), respectively.

While all of the foregoing will not apply to every case, there are arguments that multiple forms of “unprofessional conduct” are committed by physicians who are not properly trained to deal with disorders treated with ketamine. It only takes one violation from the above list for a physician to face severe consequences in Arizona.

While I have heard plenty of physicians say that ketamine is a safe drug and has been used effectively for a long time (as an anesthetic), that really misses the point. Treating behavioral health disorders is not just giving a patient prescription drugs and sending them on their way. Instead, it often requires a team of professionals to treat someone with psychiatric disorders.

Recommendations

Whenever a physician questions whether their practice conforms with the law, he would be wise to consult with a lawyer. However, there are also other “free” resources that a physician can use. We often recommend that a physician speaks to her malpractice insurer when there are malpractice or ethical concerns.

Every malpractice insurer that I am aware of has a risk management department. Their job is to prevent claims from being filed against their insureds. Since physicians pay substantial premiums, they should consult with the risk management department for advice regarding the issues raised in this post (and other issues too). Moreover, a physician should also inquire about whether their policy will cover him if he is practicing beyond his expertise. Presumably, the policy would provide coverage since the physician has to disclose his or her practice to the insurer. One would assume that if a policy is issued after all the necessary disclosures are made, the insurance would cover claims for that type of practice. But, always better to be safe than sorry.

Another way to decrease potential exposure is to take continuing medical education classes on ketamine treatments, behavioral health disorder treatments, and any other disorder being treated by the physician.

While ketamine clinics, and soon, other forms of psychedelic treatments, are becoming quite popular in the US, wise physicians will do their due diligence before treating patients with these forms of therapy. It is paramount that a physician understands the proper scope of her practice based on her training and board certification.