Over the last year and change, I’ve written quite a bit about how the ketamine telehealth industry was in store for a rude awakening when the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE) declaration ended. My most recent post, entitled “Bad News for Ketamine Telehealth” predicted an imminent shakeup in the industry due to the looming end of the PHE declaration. However, it looks like much of what I anticipated may not come to pass, as the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) just dropped proposed rules for permanent telehealth flexibilities. This is good news for the ketamine telehealth industry. I’ll unpack the rules below.

First though, I’ll give a short explainer on what led to the situation at hand. This is cribbed from our prior posts on ketamine telehealth, which I link to above and at the bottom of this post. In any event, a federal law known as the Ryan Haight Act (RHA) requires physicians to have an in-person consultation with a patient before prescribing controlled substances. This law was passed to make it harder to dispense controlled substances to unknown third parties online. The RHA’s requirements were suspended during the PHE declaration, which will end on or around March 11, 2023.

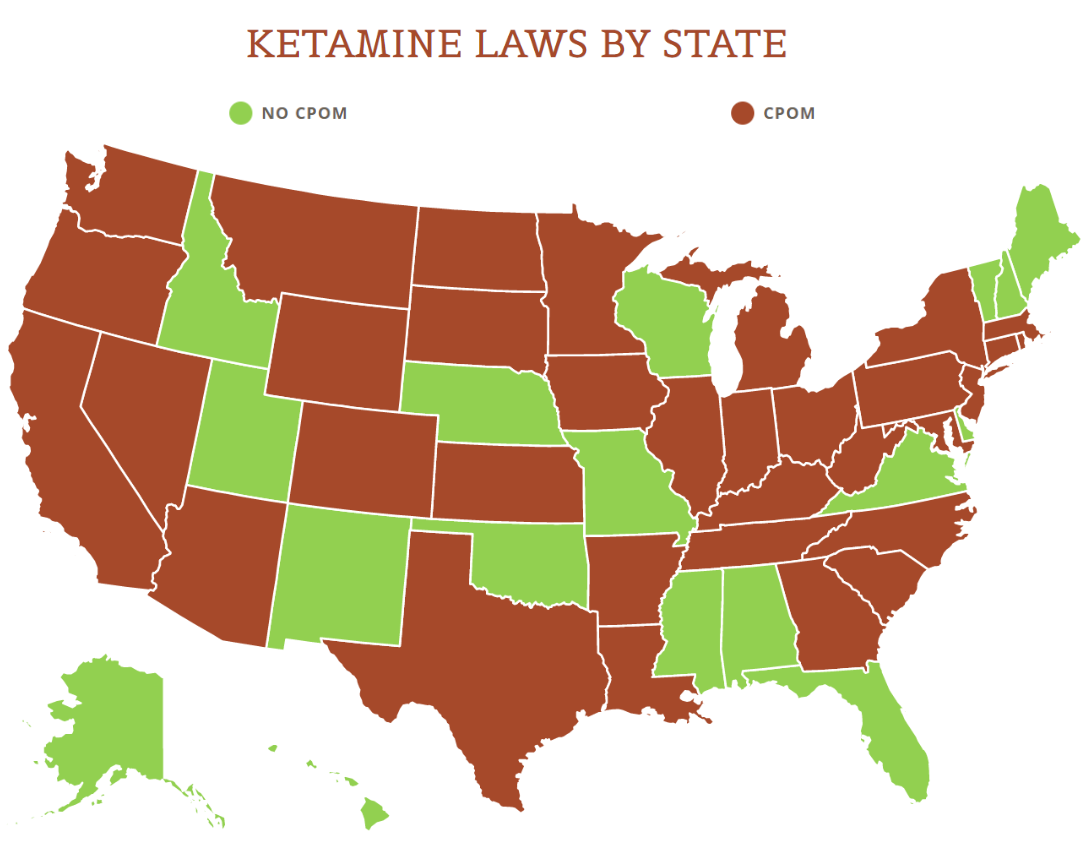

View the US Map of Ketamine Legality

To be clear, the RHA wasn’t related only to ketamine but to all controlled substances. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became clear that telehealth services in general were beneficial to folks who lived in areas with limited physician access or who otherwise had trouble accessing medical care, and a swath of groups petitioned the federal government to permanently loosen the RHA’s restrictions. Given the inability of Congress to generally get anything done, it seemed unlikely that this would ever change, or at least that it would ever change before the looming expiration of the PHE declaration. But DEA’s proposed rules aim to do just that . . . with some caveats.

Turning to the rule itself, there’s a lot to unpack. The DEA’s rulemaking package itself is more than 60 pages of text, so we won’t cover everything today. But here are some highlights from the proposed rule:

Most notably, the rule would allow practitioners located in a U.S. state or territory and with appropriate DEA registrations to issue schedule III – V controlled substance prescriptions via telehealth. Ketamine is a schedule III narcotic, and hence, ketamine telehealth clinics may be permitted to continue if they can otherwise comply with the rules. One big caveat is that the RHA will still apply and require a prior in-person consult unless an exception applies. The exceptions include: (1) the practitioner first receives a qualifying telemedicine referral from another medical practitioner who first conducted an in-person medical evaluation; (2) the practitioner is employed by the Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) and the patient received a prior in-person medical evaluation from a different DVA practitioner; or (iii) the practitioner had a telemedicine relationship established during the PHE declaration (with a big caveat that I’ll describe below).

In terms of relationships established during the COVID-19 pandemic, there are of course numerous restrictions on what qualifies. The rule applies where a practitioner hasn’t conducted an in-person medical evaluation but did prescribe controlled substances via telehealth during the PHE declaration. The kicker though is that it will apply only where “No more than 180 days have elapsed since” the later of the date the rule becomes final or the date the PHE declaration ends.

Prescribing practitioners will be able to issue prescriptions via telehealth for up to a 30-day supply of a controlled substance. This limitation won’t apply, however, to the PHE declaration relationships or to the DVA relationships. The exception also won’t apply in cases where a medical evaluation takes place. For ketamine telehealth clinics that don’t provide longer-term prescriptions or administrations, this may not be much of a concern. But all ketamine telehealth providers will need to familiarize themselves with prescription restrictions.

One of those restrictions is that prescribers must first review prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) data in the state where the patient is located. If the practitioner cannot get PDMP data, the prescription supply will be limited to 7 days until such data is accessible. Prescribing practitioners will need to note on the face of prescriptions that they are prescribed via telehealth. And both the practitioners who provide telehealth services, as well as referring practitioners, will be require to keep and maintain records, such as information about the patient at hand and the controlled substances that the practitioners prescribed. These records will need to be kept, in the case of the practitioner providing the telehealth services, at the location at which the practitioner holds his or her DEA registration (and one specific location will be able to be designated for storage for practitioners with multiple registrations).

One other key note is that the prescription process will by definition be limited. If a practitioner does not conduct a qualifying medical evaluation (which can include evaluations in the presence of third-party, DEA-registered practitioners) within 30 days after first issuing a prescription, the practitioner may not issue additional telehealth prescriptions. Again, there is an exemption for COVID-19 or DVA relationships.

Keep in mind too that the term “practice of telemedicine” will require practitioners to comply with both state and federal laws. As we’ve predicted before, even if the federal government clears the path for telehealth businesses, it will still need to follow state law. And state laws run the gamut for what they allow. What is pretty universal however is that states require licenses to practice, so we don’t expect ketamine telehealth companies to be able to operate in states where their physicians aren’t licensed. Additionally, if state law isn’t exactly in line with DEA’s rules, it could take a while until they are harmonized – if they ever are.

Finally, let’s talk procedure. DEA published the rule on February 24, 2023. There will be a 30-day public comment period (so if any folks interested in ketamine telehealth have comments, they’ll have a short window to submit them). The DEA will then have to consider public comments and may reevaluate or change rules. It’s not guaranteed that the rules will become effective at all, much less that they’ll become effective in their current form. Given that the PHE declaration will necessarily end before the rules are finalized, there will be a transitionary period with limited guidance on proceeding with relationships established during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Stay tuned to the Psychedelics Law Blog for additional updates on ketamine telehealth and the DEA regulations. For some of our older posts on ketamine telehealth, see: