A China-centric written contract is an effective tool for doing business in or with China. A first step in creating this effective tool is to carefully follow the rules for execution. Chinese courts are bureaucratic and formalistic. Make use of that tendency so you can prevail. Don’t blunt the edge of your instrument with sloppy execution procedures. Failing to follow China contract law formalities can lead to a Chinese court not enforcing your contract.

The basic rules for execution by the Chinese side are as follows:

1. The execution date must be specified for each entity that signs. Do not rely on a single date at the top.

2. The legal name of the signing entity and the legal, registered address of that entity must be stated in Chinese. Many Chinese companies only provide their common name or English-language name, or provide a business address rather than the registered address. Failing to request the proper information is a major mistake.

3. The individual who signs on behalf of the Chinese entity must have authority to sign that contract on behalf of the Chinese entity. If the individual is the legal representative of the Chinese entity, his or her authority is clear. In other cases, however, that person’s authority must be demonstrated by the title given to the individual by the Chinese entity. If that title is sufficient to show authority, the Chinese entity is bound to the contract, regardless of the individual’s actual status with the company. Care in getting this right is required. A person with the title “foreign acquisitions manager” clearly has authority to purchase from foreign buyers. But what if the title is “accounting department manager” or “research and development department manager”? It is not certain these persons have any authority to execute contracts.

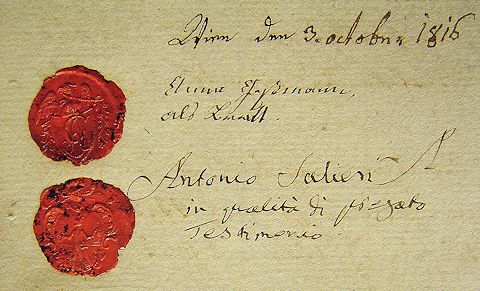

4. The contract should be stamped with the official, registered company seal. Chinese entities often have seals in addition to the standard company seal. For example, many companies have seals specifically designated for executing contracts. Such seals are acceptable, provided they are registered and individually numbered if the Chinese company has more than one, which is common. Chinese entities may have other seals, such as technical verification seals, tax department seals and banking/financial seals. These additional seals should never be used for sealing contracts. Only the official company seal and registered contract seals should be used on a China contract. Every legitimate Chinese company has documentation of the registration of their official company seal or their registered contract seal(s). Just ask for a copy. If they do not provide you that, it means they are planning to use an unofficial seal, with predictable results in the event of a dispute.

The area that causes the most confusion is the requirement of a seal. An unsealed contract is not invalid on its face but it can cause you all sorts of trouble. Chinese law on the issue of seals and contracts provides as follows:

- Article 32 of China’s Contract Law provides that contracts must be executed by the company legal representative or by a person with authority to execute the contract. It also provides that execution may be by signature or by seal.

- Article 50 of China’s Contract Law provides that if a person with apparent authority executes a contract beyond that person’s actual authority, the contract is still valid with respect to a third party who had no knowledge of the scope of actual authority.

Thus, by the terms of the Contract Law, an unsealed contract is still a valid contract if it was executed by a person with apparent authority. So why is it so important to get your China contracts sealed? The purpose of a written contract with your Chinese counter-party is to give you a tool you can use in a Chinese court to obtain swift and certain relief against a Chinese entity that has breached the terms of your contract.

The first thing Chinese courts usually do in any breach of contract lawsuit is determine the authenticity of the contract. Where a contract is sealed with the official, registered company seal, the contract is prima facie valid. Chinese courts nearly always rule against a Chinese entity that argues that the seal is false or that the seal has been lost if a registered company seal was used to seal the contract. A contract lacking any of the four elements set out above is subject to challenge. Though you may prevail on that challenge, you could face long delays. You also might not prevail and the uncertainty alone can be enough to give the Chinese company enough comfort to fight you hard and to force you into a less than favorable settlement.

But why is a seal “required” when China’s Contract Law clearly provides that a signature is sufficient? Again, this is matter of proving authenticity. It is the custom in China to have ALL contracts sealed. Every company in China, no matter the size orform of ownership is issued a registered company seal upon its formation. Chinese state owned enterprises are required to seal all contacts. This practice is followed by all legitimate private companies.

For this reason, unsealed contracts are immediately suspect. Chinese courts have a ton of experience determining the authenticity of seals. They have virtually no experience in determining the authenticity of signatures. For this reason, if a Chinese defendant questions the validity of a signed but unsealed contract, the court likely will deem the contract invalid. We are not aware of a China case where the validity of a non-sealed contract was upheld by a Chinese court in the face of a challenge. Now just imagine how the Chinese courts will treat your “email contract,” your PO/Invoice contract, or your oral contract.

What happens if the seal is not the official, registered company seal? Litigation in this area has been common in China. The usual facts involve a Chinese or foreign entity that enters a contract with a Chinese company for the provision of goods or services. The entity provides the goods or services to the Chinese company, but the Chinese company that received the benefit refuses to pay because the written contract was not properly sealed. The following are standard seal defects:

- The wrong type of seal was used: perhaps a technical seal instead of a contract seal.

- The Chinese company has many unofficial seals and one of these unofficial seals was used rather than an official seal.

- The person who signed the contract for the Chinese company is an agent of the Chinese company, but not an employee, but the seal is an official seal.

- The primary contract is improperly sealed but its supporting receipts are properly sealed.

In all of these cases, the courts have held that the company questioning the seal must prove the company falsified the seal and sealed the document with such a false seal to defraud. This burden is usually impossible to meet in cases where the goods and services have already been delivered.

The defects in these contract execution cases turned routine, six month collection cases into expensive, multi-year ordeals. Note also that in all these cases, the goods/services had already been provided. Finally, in all cases the contract or other documents were sealed in some way. We have not found any China court cases where a bare signature was sufficient.

Chinese courts are hyper-technical when working with written documents. If there is any surface flaw, a party will object to the authenticity of the document and force the party offering the document to prove its authenticity. Chinese lawyers will seek out these minor surface flaws and object to authenticity even where that objection is clearly ridiculous. The courts in China reward them for this behavior because this is a good way to clear their docket of commercial cases.

But if you follow the above rules, the Chinese courts will almost certainly find your contract authentic and you will then have leverage against your Chinese counter-party should something go wrong between the two of you. Most importantly, you will in most instances forestall an authenticity argument entirely. If you don’t follow the above rules, you will likely create uncertainty and added costs.

UPDATE. A reader wrote us to posit that the way to avoid all of the above problems is to draft a contract calling for disputes to be resolved in a U.S. or some other foreign court. Do not do this! China does not enforce U.S. court judgments so even if you prevail against your Chinese counter-party in a U.S. court, unless that Chinese company has assets in the United States, you probably will never collect a penny from that Chinese company. The same is true with respect to most (but not all) other countries. Arbitration outside China has its own special risks.