What should you do if you are owed money by or have been wronged by a Mainland Chinese company? Bring a lawsuit against the Chinese company, of course. But how?

Mainland Chinese courts do not enforce U.S. judgments. Therefore, it will probably be a waste of time for you to bring a lawsuit in a U.S. court against a Chinese company that does not have assets in either the United States or in a country that enforces U.S. judgments. However, it is important you research where the “Chinese” company is actually based because Mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macao are different jurisdictions entirely. If you can sue the Chinese company in a country other than the United States, you should research whether Chinese courts enforce judgments from that country or not.

This post discusses the challenges of litigating against Mainland Chinese companies and offers guidance in overcoming these challenges, both in the United States and in China. Much of what is said here about suing a Chinese company in a U.S. court applies equally to suing a Chinese company in other countries as well, but much can also vary depending on the country.

1. Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction will usually be the first issue you will need to resolve in formulating your litigation strategy against a Chinese company. Suing a Chinese company in the United States requires the typical contact inquiry involved in suing any foreign company. See Asahi Metal Industry Co. v. Superior Court of California, Solano Cty., 480 U.S. 102 (1987); Glencore Grain Rotterdam B.V. v. Shivnath Rai Harnarain Co., 284 F.3d 1114 (9th Cir. 2002).

An American company usually faces no jurisdictional bar to suing a Chinese company in Mainland China. Articles 3 and 237 of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China grant Chinese courts jurisdiction over international cases involving a foreign plaintiff against a Chinese company. Though suing in China is usually possible, it obviously should not be done without a better understanding of what it will actually entail.

If a U.S. court has jurisdiction over a Chinese company, suing that Chinese company in a U.S. court typically will differ from suing a domestic company on: service of process; discovery; litigation strategy; and the already mentioned enforcement of judgment.

2. Service of Process

China is party to the Hague Convention on Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil and Commercial Matters. Thus, service on a Chinese company must comply with this Convention. Service under the Hague Convention on Service is effected through the designated Chinese Central Authority in Beijing, which is the Bureau of International Judicial Assistance, Ministry of Justice of the People’s Republic of China.

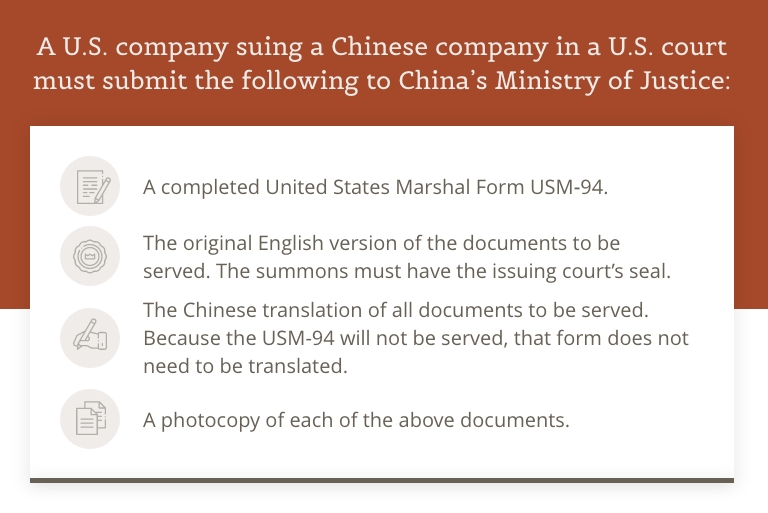

A U.S. company suing a Chinese company in a U.S. court must submit the following to China’s Ministry of Justice:

- A completed United States Marshal Form USM‐94.

- The original English version of the documents to be served. The summons must have the issuing court’s seal.

- The Chinese translation of all documents to be served. Because the USM-94 will not be served, that form does not need to be translated.

- A photocopy of each of the above documents.

Though China did not make a specific reservation regarding translations when it acceded to the Hague Convention on Service, China’s Ministry of Justice has advised the U.S. Embassy in Beijing that documents to be served in China must be translated into Mandarin Chinese. Since China’s Ministry of Justice is the government entity that effects service of process in China, it only makes sense to comply with its requirements.

China’s Ministry of Justice will send your service of process documents to the appropriate local court and that court will effect service. In our experience, Chinese courts are slow to send out service. If the Chinese company being sued is a powerful local entity, service may be even slower. Repeatedly calling and emailing both the court itself and the Ministry of Justice usually expedites service. You should figure on service taking six to nine months.

China formally objected to service by mail under Article 10(a) of the Hague Convention on Service and U.S. courts have held that objection valid. See DeJames v. Magnificence Carriers, Inc., 654 F.2d 280 (3d Cir. 1981), cert. den., 454 U.S. 1085; Dr. Ing H.C. F. Porsche A.G. v. Superior Court, 123 Cal. App. 3d 755 (1981).

Once you serve a Chinese company in a U.S. lawsuit, it will be bound by the U.S. court’s normal discovery rules. However, China prohibits depositions on its soil, even if the deponent consents. In its declaration on accession to the Hague Convention on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil and Commercial Matters, China stated it would not be bound by those provisions granting consular officers the right to oversee depositions.

In 1989, China allowed a deposition in U.S. v. Leung Tak Lun, et al., 944 F.2d 642 (9th Cir. 1991), but advised that its grant of authority for that particular deposition should not be considered precedent, and China has not permitted a deposition since. Conducting a deposition in China may lead to arrest or expulsion. Even a telephonic deposition of a witness in China likely violates Chinese law, and would not be a good idea for anyone planning to go to China. The easiest way to depose a China‐based witness is usually to have that witness go to the United States or to Hong Kong for deposition.

China has agreed to allow limited discovery of documents under the Hague Convention on Evidence. That Convention provides for document discovery via a Letter of Request issued by the court where the action is pending and transmitted to the “Central Authority” of the jurisdiction where the documents are located. The Central Authority is then responsible for transmitting the request to the appropriate judicial body for a response. That Convention allows a signatory country to “declare that it will not execute Letters of Request issued for the purpose of obtaining pre‐trial discovery of documents as known in Common Law countries.” China has executed such a declaration, making document discovery permissible for trial purposes, but not merely to gather information.

Though China has agreed to document discovery for trial, you should not expect the Chinese Central Authority will instruct a Chinese court to compel production in your case. The U.S. State Department made the following accurate summary of how China typically responds to U.S. court document discovery requests:

While it is possible to request compulsion of evidence in China pursuant to a letter rogatory or letter of request (Hague Evidence Convention), such requests have not been particularly successful in the past. Requests may take more than a year to execute. It is not unusual for no reply to be received or after considerable time has elapsed, for Chinese authorities to request clarification from the American court with no indication that the request will eventually be executed.

Chinese companies are not accustomed to U.S.-style discovery, and they often consider compliance with the discovery rules optional. Go here for a recent example of that.

3. Arbitration Outside China

China is a signatory to the 1958 Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards. This means its courts generally enforce foreign arbitral awards from recognized foreign arbitral bodies. Chinese courts, however, are considerably less likely to enforce foreign arbitral awards obtained by default. Chinese courts also sometimes stall foreign arbitration award cases for years to avoid enforcement while making their enforcement numbers look better than they really are. You will find this most likely to be true if the Chinese courts consider your award to be inequitable or if it is against a powerful company in a small town or if your company is based in a country on the outs with China.

Chinese companies know that Chinese courts are reluctant to enforce arbitration awards against Chinese companies that fail to show up for a foreign arbitration so they often fail to show up for a foreign arbitration they know they will lose. This allows them to argue against enforcing the foreign arbitration award on the grounds that they never got notice of the underlying arbitration and/or that the method by which they were given notice was improper

Chinese courts also sometimes stall foreign arbitration award cases for years as a way to avoid enforcement without hurting their enforcement numbers. This stalling is more likely to happen with arbitration awards against powerful Chinese companies or with awards that appear inequitable. Also, China’s signing of the New York Convention on arbitration was limited to enforcing only awards from another New York Convention state that arose from a commercial legal relationship

a. Procedure for Enforcing Foreign Arbitration Awards.

If you prevail in an arbitration outside China and you want to enforce that award in China, your next step is usually to go to the appropriate Chinese Intermediate Court (usually the one in the location where your defendant resides) with the following:

-

- A written application requesting it enforce your award by converting it to a court judgment.

- An apostilled and consularized original of your arbitration award.

- The original agreement that contains the arbitration provision that allowed you to pursue arbitration. This too should be apostilled and consularized.

- Chinese translations of the above documents and whatever else you will be submitting to the Chinese court.

The Chinese court can deny your request to enforce your foreign arbitration award on the following grounds:

-

- Lack of a valid arbitration agreement.

- The Chinese company was not served with the arbitral proceeding or given notice of its opportunity to appoint an arbitrator, or it did not have the opportunity to present a case for reasons not of its own making.

- The arbitral tribunal or the conduct of the arbitral procedure was not in line with the arbitration rules.

- The matter arbitrated was not arbitrable or was outside the scope of the arbitration agreement.

- Enforcing the arbitration award would be contrary to China’s social and public interests.

If you think some of the above provisions are vague or broad enough for a Chinese court to drive a proverbial truck through, you would be right. It is fairly easy for a Chinese court to come up with good grounds for not enforcing an arbitration award. We estimate Chinese courts enforce maybe 90 percent of foreign arbitration awards, and some of the ten percent of awards not enforced are due to the company seeking enforcement having not done everything correctly.

4. Arbitration in China

China has some legitimate arbitral bodies, with the China International Economic Arbitration Commission (CIETAC) probably being the most prominent. China’s arbitral bodies allow little to no discovery and they oftentimes do not even allow live testimony. Even if live testimony is allowed, you should expect your case to be won or lost on the documents.

If your contract with your Chinese counter-party is going to call for arbitrating disputes in China, it will typically make sense for you to provide for English language arbitration and as many foreign arbitrators as your Chinese counter-party will accept.

5. Suing in a China Court

If suing a Chinese company in the United States does not make sense (see the above on enforcement of U.S. judgments in China as to why it usually does not), pursuing litigation in China may. Though China’s court system is very different from that to which American lawyers are accustomed, it is more navigable than many American lawyers believe it to be. Foreign companies can and do win cases against Chinese companies in Chinese courts. Before suing in a Chinese court, though, it is important to understand some basics about its court system.

First, though Chinese courts will enforce the law prescribed in a contract, Chinese judges place more emphasis on the overall context and “fairness” of the case and much less on legal technicalities than their American counterparts. For example, if an incompetent or uncaring low-level employee causes a company to violate its contract, a U.S. court would almost certainly hold the company liable for all damages arising from the breach. A Chinese court, on the other hand, might not find liability at all or severely limit the damages, believing it unfair to penalize a company for the incompetence of one employee.

Second, Chinese courts prohibit nearly all discovery. Companies suing in China without a strong case at the outset seldom prevail. This means you should have your proof ready to go before you sue in China, especially since the time from filing to trial is usually less than a year.

Third, Chinese courts base their rulings almost exclusively on documentary evidence, not testimony. So as we said about arbitration in China, you should be prepared to win or lose your case based on the documents. This means you need to have your documents ready before you sue or if sued, you better get your documents ready as soon as possible. This is critical because oftentimes “having your documents ready” means they must be appostilled somewhere outside China and then consularized by the appropriate Chinese Consulate or Embassy.

We cannot stress enough the need to move quickly in getting documents apostilled and consularized for a Chinese trial. Twice in the last year, American companies have called one of our China lawyers asking how they can appeal Chinese lawsuits they lost because — in their own words — they were not able to get critical documents documents apostilled and consularized soon enough to be admitted into evidence by the Chinese court for the trial. If you are an American company suing a Chinese company in China, it therefore oftentimes makes sense to have both a U.S. licensed and a Chinese licensed lawyer on your case, especially at the beginning.

Fourth, settlement is rare in Chinese business litigation matters. The cost of litigating in China is typically much lower than in the United States, and once a complaint has been filed, settling a case is often viewed as losing face. The Chinese company you are suing may prefer to lose the case and blame it on the judge than settle it and be viewed by its employees and customers as having been at fault.

Fifth, Chinese courts rarely issue large damage awards, no matter the case and no matter the plaintiff. Chinese companies generally operate at low margins and Chinese courts are loath to badly harm a functioning business or to cause layoffs. In particular, Chinese judges are hesitant to award damages for lost profits or for pain and suffering. This is gradually changing.

Chinese courts simply do not award the sort of damages available in a U.S. court. This is one of the reasons why we so often put liquidated damages provisions into our China contracts. See China Contract Damages Done Right.

Sixth, though the ability to collect on judgments in China is improving, it is still nowhere near the level of the United States. Chinese courts often lack the authority and fail to receive the assistance from other law enforcement agencies necessary to enforce collection on their judgments. Smaller Chinese companies sometimes find it more cost effective to avoid a judgment by shutting down and re‐opening under a new name. In other words, just as is true in the United States, you should consider the collectability of your judgment before you sue in China, only more so.

6. Litigation Strategies

Companies that sue Chinese companies in their home country courts usually will have many advantages over the Chinese company defendant. This is particularly true in countries (like the United States) where juries can hear your dispute. Jurors (and even judges to a lesser extent) generally view Chinese companies unfavorably.

Chinese companies frequently try to skirt foreign discovery and court rules and bringing this to the court’s attention often can cost the Chinese company credibility or force it to incur sanctions. Perhaps most importantly, Chinese companies generally underestimate the importance of foreign trial court decisions, often holding back on vigorously defending a lawsuit until appeal.

7. Foreign Court Judgments In China.

U.S. judgments usually have little value in China. There is no treaty nor a reciprocal arrangement between China and the United States regarding recognition or enforcement of civil judgments. For these reasons, Chinese courts usually disregard U.S. judgments. See China Enforces United States Judgment: This Changes Pretty Much Nothing. This Chinese court lack of enforcement is not true of all country’s judgments, especially those from the approximately forty countries that have an enforcement of court judgments treaty with China. China also generally enforces court judgments on a reciprocal basis from countries that clearly enforce Chinese court judgments.

a. Enforcing Your Foreign Court Judgment in China.

If you have a foreign country court judgment you want enforced in China, your Chinese court application to enforce that judgment must include the following documents, all in or translated into Chinese:

-

- A written application for enforcement.

- Your identification certificate or business registration certificate. If your company is a foreign business, you must must also produce the ID certificates of your authorized representative or primary responsible person.

- A power of attorney.

- An original copy of the foreign judgment or ruling or its certified duplicate and its translation into Chinese.

- For default judgments, a certificate that the party that failed to show up at the hearing/trial was legally summoned to the hearing

Chinese courts accept only certified translations and most Chinese courts have a list of the translation agencies whose certified translations they accept.

The judgment or ruling and the legal summons must be notarized by a local notary and apostilled in the foreign country where the relevant documents were generated. And they then must be certified by the correct Chinese consulate or the Chinese embassy in that country.

If the Chinese company you are suing has assets in the United States or in another country that generally enforces U.S. judgments (such as the United Kingdom, Taiwan, Canada, or South Korea), suing in a U.S. court may be the best way to proceed. If that is not the case, it usually makes sense to sue somewhere else, if you can. See Enforcing US Judgments in China. With other countries, research into the likelihood of China enforcing your judgment should be undertaken before you sue, not after.