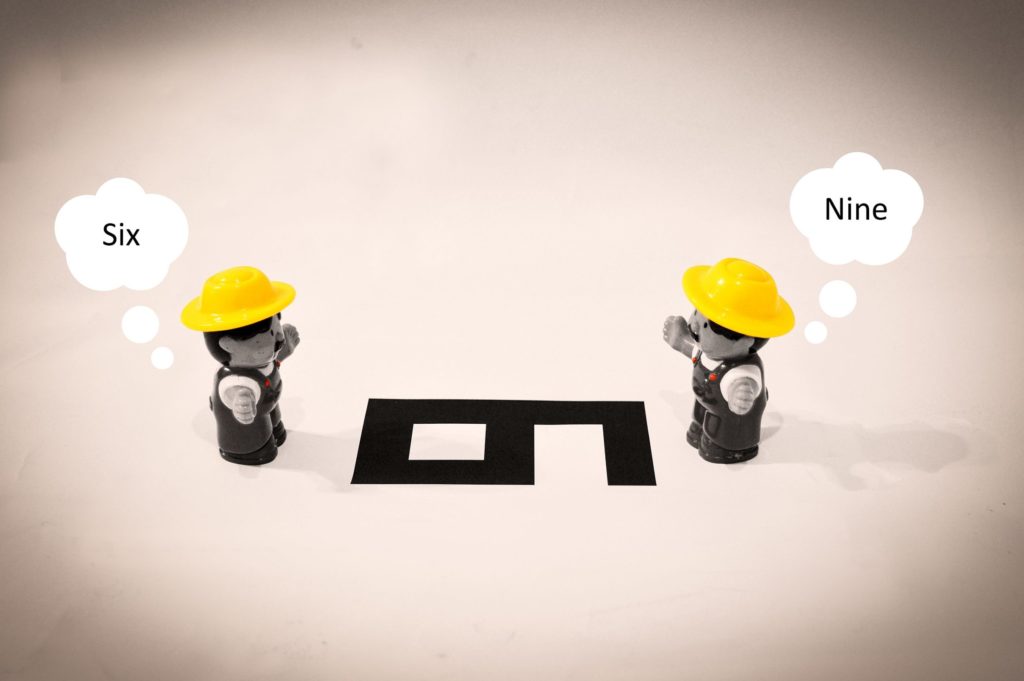

One of the less endearing featuresof the Chinese trademark system is that the Chinese Trademark Office (CTMO) and the Chinese court system have different standards for what makes one trademark “confusingly similar” to another, which is the statutory basis for determining whether one trademark conflicts with another. To make things even more confusing, neither the CTMO nor the Chinese court system has a uniform, clearly articulated standard.

That being said, experienced practitioners know CTMO examiners are generally stricter than Chinese judges. The CTMO continues to hire vast numbers of inexperienced trademark examiners who are under tremendous time pressure to crank through a huge number of trademark applications. They’re following a playbook, just like an offshore customer service representative, and they aren’t rewarded for making appropriate judgment calls. I haven’t been to one of their training sessions, but I have to believe the mantra drilled into new recruits is “When in doubt, reject.”

None of the CTMO examiners are native English speakers and many don’t speak English particularly well. They are trained to look for similarities in phonetics, pronunciation, appearance, and meaning, which can lead to absurd results for English-language marks that superficially appear similar. For instance, “Big Work” and “Big Dork” might well be considered confusingly similar brand names by the CTMO even though there isn’t a single native English speaker who would ever confuse the two. In fact, the CTMO would probably consider “Work Big” and “Big Dork” to be confusingly similar. At a very high level, you can see why: the order of the words is flipped and one letter is different, but otherwise they are identical.

It’s possible to rationalize the CTMO’s unsophisticated approach to English-language trademarks by noting that many Chinese consumers have limited English-language skills and might indeed think that “Work Big” and “Big Dork” brands were produced by the same company. But this argument doesn’t hold up under further scrutiny, because the CTMO examiners take the same approach with logos (that are not in any particular language).

The Trademark Review and Adjudication Board (TRAB) hears appeals of trademark rejections, and they have a more objective and sensible approach to the “confusingly similar” standard. But they, too, are overworked and understaffed, and far more often than you might expect, they will uphold a ridiculous CTMO decision. So it is entirely possible that in real life, an existing registration for “Work Big” would block an application for “Big Dork.”

Meanwhile, the Chinese court system would almost certainly not find that the “Big Dork” brand infringed upon the “Work Big” registration. The owner of “Work Big” could not get an injunction or damages, and would be hard pressed to take any action at customs. Frankly, it probably wouldn’t even occur to them because the marks are so different.

So where does that leave the owner of the “Big Dork” brand? They are unable to secure a trademark registration in China, but they can’t be sued for infringement either. Effectively, they’re in the same position as anyone using a descriptive trademark: nobody can stop them from using it, but they can’t stop anyone else from using it either.

Whether this is acceptable to the “Big Dork” brand owner largely depends on what they want to do in China. If all they want to do in China is manufacture goods and be assured that their goods will not be seized at Customs for alleged trademark infringement, they should feel reasonably confident. It’s not ideal, though, since CTMO’s decisions are not binding and if a trademark squatter files an application a couple years down the line and gets a CTMO examiner with a more relaxed standard, that squatter might be able to secure a registration after all. The best decision would be to use a trademark that they could definitely register in China, whether by appealing the CTMO’s rejection or by picking a new trademark. Better safe than sorry.

And if they plan to sell goods in China, they absolutely need to find another trademark, because it’s guaranteed that someone else would copy the “Big Dork” brand name and they wouldn’t be able to do a thing about it. See Make China Trademarks a Priority.