Service of Process Companies and Domestic Litigators Should NOT Apply

Many years ago, I read an excellent blog post over at the Letters Blogatory blog, Service of Process and the Unauthorized Practice of Law, on how service of process companies frequently mess up to the detriment of their clients. This post also asks whether these service of process companies are engaging in the unauthorized practice of law and hints that they are.

The post starts out talking about the lawyer-blogger’s recent experiences with international service of process botched by service of process companies:

I have come across several cases recently where a plaintiff, or more likely the plaintiff’s lawyer, had hired a “vendor” or a contractor to serve process abroad, and where it seemed clear to me that the “vendor” had given the client bad advice or where the vendor had not done a good job effecting the service. For example, I’ve seen vendors submitting requests for service to a foreign central authority and then, after the client asks why service hasn’t been completed, informing the client that service in the country in question might take a year. The client then moved for leave to serve by alternate means, which is perhaps what the client should have done in the first place with its money. Or else I’ve seen a vendor lash out at a foreign central authority’s refusal to execute a request for service rather than try to understand the legal basis for what the foreign central authority is saying.

The international litigation lawyers at my law firm have recently seen a quasi-onslaught of bad or delayed service of process attempts on Chinese companies, both by service of process companies and by domestic litigators who lack experience with international litigation. We typically see these sorts of things at about year one of failed service when the client-company turns to its lawyer and says: “it’s taken more than a year and we are nowhere in effecting service, would you please find someone who can help us on this?” Their lawyers call our law firm and we then figure out why service has yet to have occurred.

The blog post then starts asking questions about whether these service of process vendors may be operating outside the law by practicing law without a license: “To what extent do the things we do in international service of process constitute the practice of law? Or conversely, to what extent are the “vendors” doing things they shouldn’t be doing unless they are lawyers?”

Good theoretical questions, to which I will eventually provide a very practical “answer” below. The post then posits how serving process is not the practice of law when it consists of little more than going to someone’s house and handing them court papers. I 100% agree because, as the post notes, this does not involve any “real legal judgment.” But as noted in the post, “the decision of what form of service to use, especially in cases of service abroad, is most certainly a decision that requires legal judgment, at least in many cases”:

Suppose you say you want to serve via the foreign central authority. There are some logistical questions about how long the process will take, what fees must be paid, etc. But there are other more significant questions for the lawyer: Will the methods of service the foreign state is likely to employ satisfy due process requirements in the US? Does the case seek the kind of relief, e.g., punitive damages, or is it the kind of dispute, e.g., a tax dispute, that will lead certain foreign states to refuse to execute the request? And if you want to use an alternate method of service permitted by the Convention, similar questions arise.

To we China lawyers, the “money” portion of the post is when it discusses a vendor who spends a long time trying to effect service, only to mention after getting paid and after having submitted the service of process request to China’s central authority how incredibly long service of process is now taking on Chinese companies. Those were most certainly the good old days, however, as it is typically taking about a year now. There is also the very real issue in any United States case against a Chinese company as to whether the case is even worth pursuing, because so often it is not. See China Enforces United States Judgment: This Changes Pretty Much Nothing. That will be the topic of my next international litigation blog post because we have been getting a ton of lawyers calling us up lately thinking that enforcing a U.S. judgment in China will be a piece of cake when in fact it will be anything but.

Now for my practical answer on the unauthorized service of law question. The real issue is not so much whether these service of process companies (which are typically great for serving process domestically) are engaged in the unauthorized practice of law or not. To me the issue is whether you as a company want to entrust your multi-million dollar (or even $200,000) case to a non-lawyer to figure out the best way to effect service that (1) complies with the Hague Convention, (2) satisfies the requirements of the court in which your lawsuit is pending, and (3) the foreign country in which the defendant is going to be served. And if you are a domestic litigation lawyer facing these same issues, do you a year down the road want to explain why you used what is essentially a specialized messenger service to effect complicated international service? I sure wouldn’t.

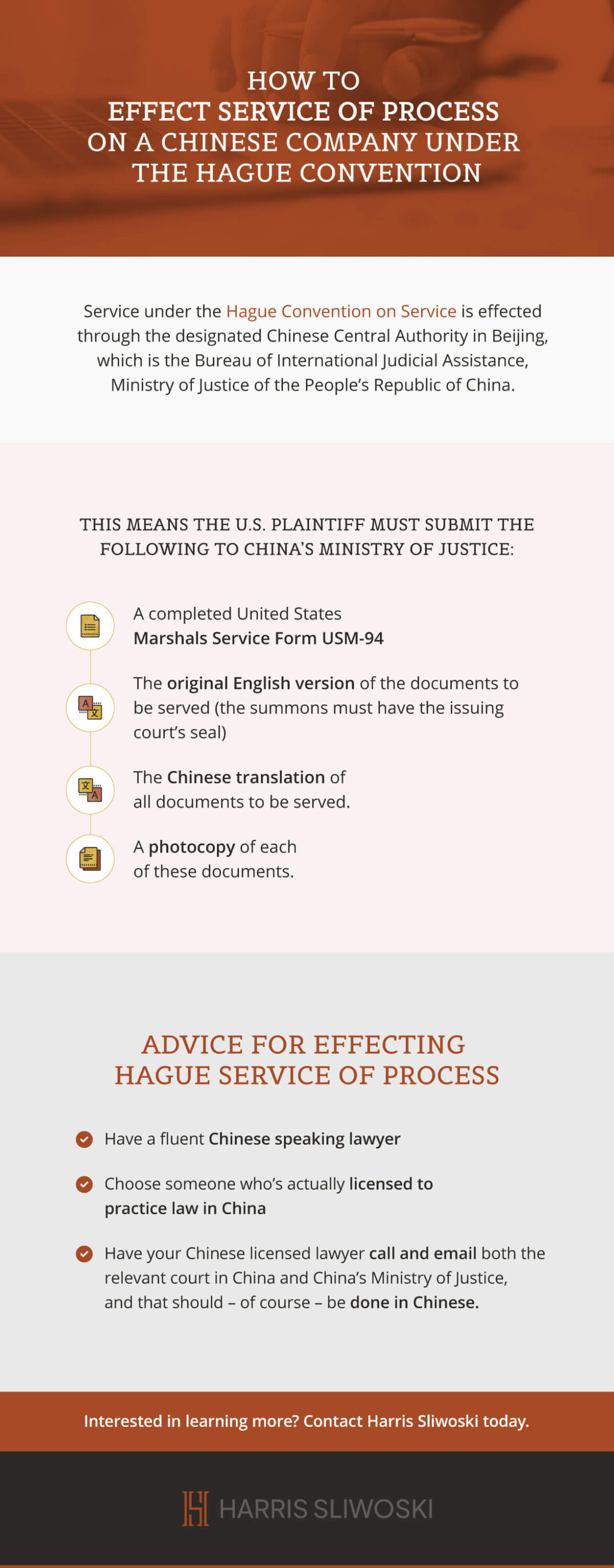

How to Effect Service of Process on a Chinese Company under the Hague Convention

1. A completed United States Marshals Service Form USM-94

2. The original English version of the documents to be served (the summons must have the issuing court’s seal)

3. The Chinese translation of all documents to be served.

4. A photocopy of each of these documents.

Note that because the USM‐94 will not be served, translation of this document is not necessary. In addition to the documents, a payment of approximately US$100 by an international payment order must be sent with the service request, payable to the Supreme People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China. It is imperative you get all of the above 100% correct as our international litigators are often retained by law firms that did not even learn why service was not occurring until 10-14 months into the process, at which time they had to start again.

The Ministry of Justice then sends the service documents to the appropriate local court, and that court will effect service. Chinese courts are often fairly slow to send out service. If the Chinese company being sued is a powerful local entity, the service may be even slower.

Truth is that even if you comply with all of the above, the real trick to effecting Hague service of process on a company or individual in Mainland China is to have a fluent Chinese speaking lawyer (preferably a lawyer who was — or still is — actually licensed to practice law in China) repeatedly call and email both the court itself and the Ministry of Justice in Chinese. Generally, both the court and the Ministry of Justice prefer dealing with lawyers (not translators or even paralegals) who both speak and write in Chinese.

Service on a Chinese company by mail is not effective and U.S. courts have held that China’s formal objection to service by mail under Article 10(a) of the Convention is valid. See DeJames v. Magnificence Carriers, Inc. and Dr. Ing H.C. F. Porsche A.G. v. Superior Court.