Cautionary China Tales and Key Strategies

Doing business in or with China comes with hidden risks, but due diligence can mitigate them. This post explores real examples of overseas missteps, the importance of safeguards, and the key steps you should take to ready your organization for new territories.

As companies reconsider their China strategies, it’s crucial to understand the unique risks and requirements for operating there. In this post, we’ll share cautionary tales and best practices based on our experience assisting foreign firms in China.”

China’s Growing Risks

China presents unique challenges for foreign companies. As foreign businesses adapt their strategies in the country, it’s important to be aware of the changing landscape. Any significant move by foreign companies draws close attention within China.

Our firm often has to inform clients that the China entity or IP they thought they had does not exist, or that the contract they thought protected them is entirely worthless. While some companies are leaving entirely, others are minimizing their footprint. Both paths have challenges. Moves elicit reactions – corporately and from Beijing. There’s tension; businesses feel pressure, while China assesses what’s lost. Companies must verify registrations and rights are unambiguous. Before restructuring China operations, be certain of solid legal grounding.

Classic China Examples

1. The Billion Dollar Company that Didn’t Exist

About a decade ago — before China got so much better at spotting such things — we were retained to help a U.S. company whose China general manager had stolen funds from its China subsidiary. Our investigation quickly revealed there was no China subsidiary. No China entity had ever been formed even though the China operations were manufacturing more than a billion dollars of product a year, with around 300 “employees.” The general manager had lied about having formed a WFOE, no China taxes had ever been paid, and every “employee” had been working illegally.

2. The Billion Dollar Company that Didn’t Exist, Part 2

Also, about a decade ago, a stock exchange became suspicious of one of its recent IPOs and they asked my law firm to investigate the Chinese company that had IPO’d. This company sold high-end fashion products aimed at 25-35-year-old professional women, and it allegedly had more than 3,500 stores. The company was based in Shandong Province.

The first thing we did was ask a very fashionable female attorney in Qingdao what she knew about this company. Because she was in Shandong Province and of THE demographic for this company and its products, we assumed she would know of it, but she didn’t. She said she would ask her friends and none of them knew of it either.

So we dug deeper, and we found that this company was a tiny company that made low-end cheap products it mostly sold at low prices wholesale. Near as we could tell, it did not have a single retail outlet, much less 3,500. The stock exchange expected the company would have issues, but nothing like this. I believe its owners pocketed the money from the IPO and were never heard from again.

3. Lost in Translation: The U.S. – China Joint Venture

A U.S. company once contacted us because its China joint venture company had started selling its product in the United States in direct competition with the U.S. company. We were tasked with determining whether this company’s China joint venture agreement gave the U.S. company the power to stop U.S. sales. The problem was that the Chinese language “joint venture agreement” was actually a consulting agreement and no joint venture had ever been formed. Our client had absolutely no recourse.

4. Non-Existent Trademarks

A Norwegian company once came to us looking to sue its former China distributor for manufacturing and selling the Norwegian company’s products in China, “in violation of our China trademarks.” The Norwegian company told us how its former distributor had registered its brand and product names for it in China, and the Norwegian company even had trademark certificates to prove this. The trademark certificates turned out to be fake and the trademarks had actually been registered in the name of a Chinese citizen (probably a relative of the distributor), who was now licensing them to the former distributor.

5. Non-Existent Trademarks, Part 2

Over the past five years, we’ve assisted numerous companies in either exiting China or minimizing their presence there. One of our initial steps is to verify the status of their Chinese trademarks. In approximately one out of every fifteen cases, we find that our client doesn’t actually possess the Chinese trademark they believed they had. Instead, it’s held by a local Chinese brand. This poses a significant challenge. If our client attempts to end or even scale down their partnership with a Chinese firm that covertly owns their trademark in China, retaliation is almost certain. The Chinese firm can prevent our client’s products from leaving the country, claiming a trademark infringement. When we find this to be the case, we work with our client in reformulating their China exit or scaling down strategies.

In the above examples, the companies were fooled by people they knew. Equally common is the situation where a foreign company pays someone it does not know to register a company or IP in China (or elsewhere) but nothing ever gets filed. There are even fake law firms that collect money from foreign companies to register their IP or their company and then pocket the money and do nothing. These fraudulent companies exploit those without international experience, pocketing payments but never delivering services. They mirror unscrupulous manufacturers that abscond with client money without providing goods. See China’s Most Common Scams.

The Importance of China Due Diligence

In addition to the above cases involving dishonesty, we also often deal with clients who for whatever reason — oftentimes rapid growth — have failed to stay current with necessary international registrations.

Verifying your international entity and intellectual property registrations is quick, simple, and affordable. If you have even the slightest doubts, get them reviewed immediately.

A China Due Diligence Checklist

Conducting thorough due diligence can help avoid costly missteps. Here are some key items to check:

- Verify registration documents for overseas entities directly with government sources

- Conduct background checks on potential partners and key employees

- Confirm intellectual property registrations are properly filed and owned by your company

- Review all contracts and agreements in detail with experienced international counsel

- Inspect facilities, operations, and inventory of entities you plan to acquire

- Analyze financial statements and tax filings going back several years

- Interview current distributors and sales channels to assess relationships

- Search court records for pending litigation involving target entities

- Confirm required business licenses, regulatory approvals, and certifications

- Review corporate records and documents for any modifications or irregularities

- Confirm bank accounts are properly registered and owned

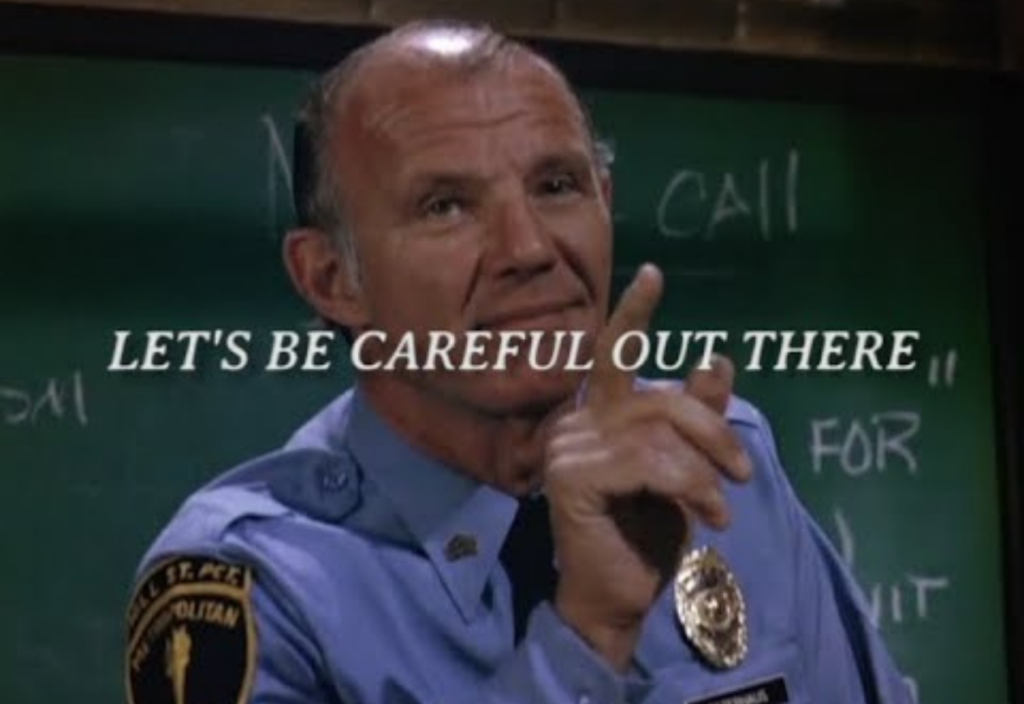

A Call to Action

By learning from past mistakes, prioritizing due diligence, and securing assets in advance, companies can improve their chances of surviving an increasingly difficult China. Knowledge is power, and proactive measures can prevent pitfalls. As the China landscape rapidly shifts, it’s crucial for you to be vigilant.

Don’t become the next cautionary tale. Now is the time to take stock of your China position and to take action to safeguard your interests and be sure to do this before making any major moves.