State legal cannabis businesses are used to the specter of the federal government in the rear view mirrors of their lives and businesses. Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you know that cannabis remains federally illegal. And it’s not so much the case anymore that the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) or Department of Justice (DOJ) are coming to knock down your door and arrest and prosecute you as a cannabis business owner for open violations of the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA). These days, life can be fairly miserable as a cannabis business owner due to the legal conflict between the states and the feds, resulting in a lack of access to financial institutions, onerous federal income tax obligations, no federal trademark protection, asset forfeiture, etc.

Rarely, though, do we get to see a state agency and the feds openly fight over these commercial cannabis democratic experiments (which is mainly due to the acting Attorney General’s “hands-off” approach to state legal cannabis, “Second Requests” scandal notwithstanding). When these confrontations happen, it’s fascinating to see how the respective governments behave and is always educational regarding evolving federal enforcement priorities.

And that is what made last week’s new so interesting. It seems that a beef has developed between the DEA, DOJ, and California’s Bureau of Cannabis Control (BCC), which the BCC oversees and licenses retailers, labs, distributors, and delivery companies in California. Keep in mind that to warrant federal attention at this point (at least per the rescinded 2013 Cole Memo and U.S. A/G Barr’s testimony regarding the same) a cannabis business would likely need to be engaged in fairly serious criminal conduct beyond just trafficking in cannabis pursuant to a state-issued license.

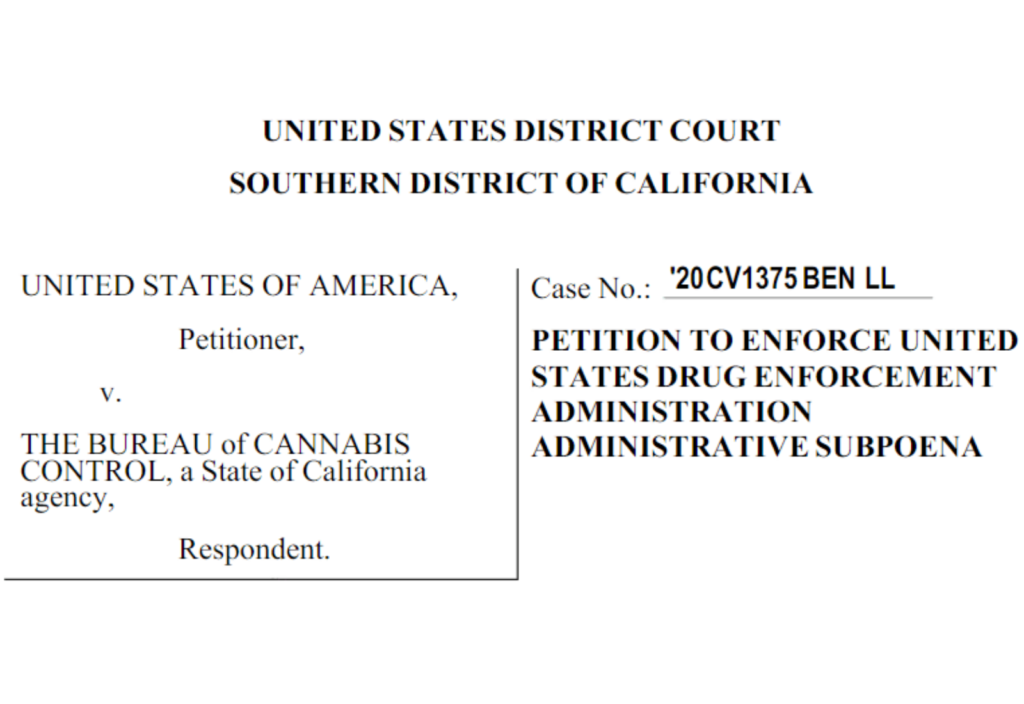

The basic gist of the fight between the feds and the BCC (per the DOJ’s July 20th court petition filing) is that the DEA and DOJ want specific information about six “entities” (which really means three corporations and each corporation’s “presumed owner”) that hold BCC licenses. The feds are conducting a criminal investigation (for violations of the CSA), and the BCC is refusing to provide that information.

Specifically, at the end of last year, the DEA served an administrative subpoena on the BCC (which it later withdrew and then re-issued an identical subpoena in January of this year) requesting unredacted cannabis licenses, cannabis license applications, and shipping manifests for these licensees from January 1, 2018 (when licensing began in California) through January 9, 2020. In the January subpoena (which is standard and boilerplate), the DEA wrote that “the information sought . . . is relevant and material to a legitimate law enforcement inquiry . . .”

In response, the BCC responded (via letter) that it wouldn’t produce the desired documents because the subpoena “does not specify the relevancy” and requested information that is “confidential, protected, and part of pending licensing investigations.” The DEA then, for a matter of months, tried to persuade and negotiate with the BCC and the California Attorney General to cooperate, but the BCC wouldn’t budge, so the feds took the matter to federal court for enforcement of the subpoena against the BCC.

In its July filing, the DOJ/DEA mainly relies on DOJ/DEA compliance with its subpoena power and authority to investigate pursuant to the CSA, the corresponding procedural components, and that all was in line with the Fourth Amendment (which institutes a “reasonableness” requirement based on relevancy and scope of the subpoena, itself). The DOJ/DEA also uses the Supremacy Clause in its arguments to bypass the application of any California cannabis or privacy laws or regulations previously touted by the BCC in its letter earlier this year.

In response to the DOJ/DEA petition, on July 29th (as first reported by Marijuana Moment with a copy of the filing), the California Attorney General fought back, arguing that the DEA/DOJ failed to prove either the relevance or reasonableness of the subject subpoena (and also revealed that the DEA/DOJ is targeting distributors in this investigation). Importantly, the BCC admits that the DEA/DOJ complied with procedural requirements and that the DEA has the requisite authority from Congress to investigate violations of the CSA accordingly.

The BCC’s lone (and probably best) attack under federal law is that the DEA/DOJ failed to prove that the requested records are “relevant to the investigation,” and that the DEA “failed to include a statement [in the subpoena] describing how the subpoenaed records are in fact relevant to the DEA investigation.” California is taking the position that, at minimum, the DEA needs to produce an affidavit of an investigating DEA agent as to how and why the requested records are relevant to the current criminal investigation. The DEA’s/DOJ’s position on this is that the subpoena on its face demonstrates the records’ relevance to the DEA investigation.

The California A/G also cited California State laws regarding confidentiality, trade secrets, and privacy laws as justifications for non-disclosure, but it’s seemingly only raising those “defenses” in its role as a state administrative agency that’s obligated to take those positions regardless of federal law.

The main question at issue in this case is whether the subject subpoena demonstrates relevance on its face without further substantiation by the DEA (namely, via an affidavit by an agent on the investigation). My take is that the BCC will likely lose this battle and will eventually have to comply with the subpoena. The reason being that federal courts have no choice but to enforce federal administrative subpoenas unless (and this is a big unless) “the evidence sought by the subpoena is plainly incompetent or irrelevant to any lawful purpose of the agency,” which is a pretty low bar. On this point, DOJ/DEA cite to solid federal case law regarding how “unconstrained” this relevance standard is in application regarding administrative subpoenas. Plus, there is no requirement under federal law that a subpoena be accompanied by an affidavit or a declaration to achieve relevance.

While we’re certainly proud of the BCC for defending itself and forcing the DOJ/DEA through the paces of total and complete compliance around the federal administrative subpoena power, this isn’t one where we see the federal court siding with the State of California (but we’d be happily surprised if it did!). Several interesting things are bound to come out of this case/investigation, and this highlights most for cannabis businesses (especially in California) that the feds are indeed alive and well and still watching.